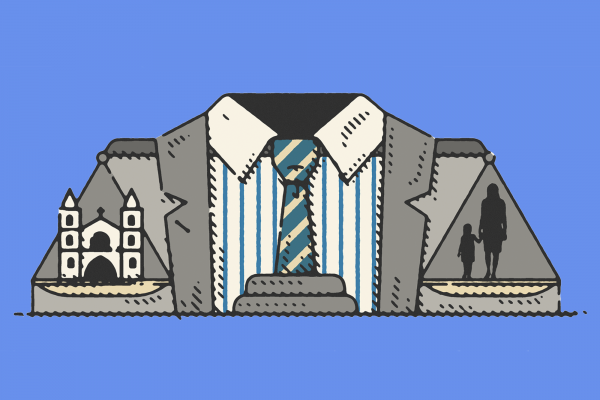

IT MIGHT NOT be a violation of professional legal ethics to participate in the Roman Catholic Church’s campaign to escape financial responsibility for the genocide of Indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States. But it is a violation of Christian ethics. And for Christian attorneys, the latter should take priority.

The Catholic Church is not the only Christian denomination from which survivors of abuse in church-run residential schools are demanding justice. Episcopalian and Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other churches also ran residential schools in North America. However, the Catholic Church ran nearly three-quarters of the residential schools in Canada and more than 20 percent of the 367 Indian boarding schools in the United States. Since May, more than 1,300 suspected graves have been identified near five former Indian residential schools in British Columbia, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan. Four of those were run by Catholic institutions.But thanks to the Catholic Church’s lawyers, it has largely succeeded at avoiding financial accountability for its legacy of violence.

Read the Full Article