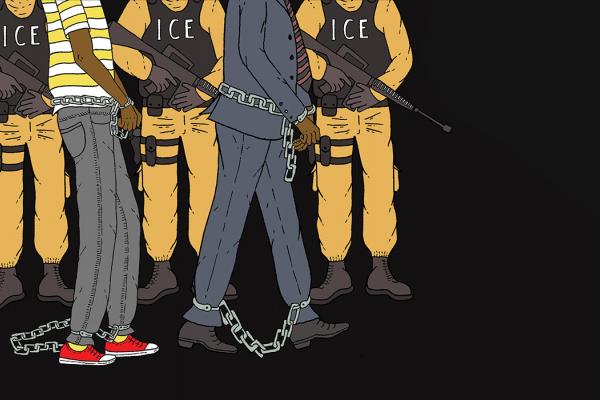

THE YEAR 2019 marks 400 years since a boat carrying “20 and odd” enslaved Africans landed at Point Comfort in colonial Virginia. To commemorate this and other historic 1619 events, Virginia will host “American Evolution,” a yearlong celebration in which these events have been transmuted into national values. The arrival of enslaved Africans on American shores has become “diversity.”

Yet, last summer a West African immigrant was deported back to Africa to face slavery, in a transatlantic reversal of journeys that underscores the persistence of immorality in this involuntary passage.

On Aug. 22, Seyni Diagne, a 64-year-old immigrant battling kidney cancer and hepatitis B, was deported from Dulles International Airport in Virginia to his home country of Mauritania after 17 years in the U.S. There he faces enslavement through forced labor. Mauritania has one of the highest rates of slavery in the world, impacting more than 40,000 black Mauritanians.

The day following Diagne’s deportation was the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. The Commonwealth of Virginia chose to mark it by recognizing the first Africans in English North America.

Efforts in the U.S. to commemorate transatlantic slavery, those who endured it, and its eventual end ring hollow against the backdrop of the Trump administration’s racist immigration and refugee policies and state governments’ compliance. Celebrating “diversity” while turning dutifully as a cog in the system that seeks to root it out is absurd. Like noisy gongs or clanging cymbals, such efforts strike a discordant note, deaf to slavery’s history and reality.

Slavery’s end is sacrosanct in the constellation of American civil religion. It is broadly understood as having confirmed the identity of the nation, justifying and sanctifying America’s leadership in the free world. The abolition of slavery is regarded as the moral apex of U.S. history, yet it is largely absent from official public discourse addressing contemporary realities of freedom and freedom of movement, including modern slavery, forced displacement, immigration, and global migration.

This absence speaks volumes. For centuries, Africans were kidnapped and brought to the U.S. in chains and faced a life of enslavement. Today, Africans come to the U.S. seeking refuge from such fates—and are being sent back.

Black Mauritanians sought safety in the U.S. from their government, which not only persecuted them but also rescinded their citizenship and refused to issue travel documents, rendering them stateless. While Mauritanians, including Diagne, found relative refuge and community in Columbus, Ohio, that safety is ending. At least 80 Mauritanian immigrants were deported in 2018.

For several reasons, Diagne’s deportation is a signal. It highlights the callousness of a U.S. immigration system that routinely ignores human health and human rights, unashamedly displaying the “moral turpitude” that it claims resides in the migrants it polices. It reveals the connections between migration policy and racism, inside and outside of the U.S. It illuminates the continuing reality of slavery and black enslavement.

For those of us who count ourselves activists, Diagne’s deportation, and the failure of airport activists who sought to prevent it, also illustrate sobering realities in the struggle for justice. Five activists went to Dulles on the night of Diagne’s deportation to plead with passengers on his plane, airport employees, officials, and others to stop his flight. Their inability to do so contrasts with what happened a month prior in Sweden when university student Elin Ersson stopped the deportation of an Afghan asylum seeker by refusing to take her seat on a plane until he was removed. Diagne’s deportation pinpoints the power of one in building moral community, and the fragility of such community. It raises questions about the failure and disintegration of solidarity and the responsibility we all bear.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!