Editors’ note: This article appeared in Sojourners magazine in 2018. In 2020, a Washington Post article by Will Hobson raised concerns about some of Bennet Omalu’s conclusions on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Ongoing research suggests that CTE is a risk for NFL players, but the rate and severity of the brain disease among football players is still being studied.

DR. BENNET OMALU is well-acquainted with gruesome deaths. “Some people wake up in the morning, put on their suits, go to offices, and to do things associated with life, with living. But me,” Omalu says from behind the office desk in his Sacramento-area home, “I dress up, I go to work to do things associated with the greatest weaknesses of [humanity].”

A forensic pathologist and neuropathologist who earned degrees in his native Nigeria and in various schools across the U.S., Omalu was most recently in the news for performing an independent autopsy on Stephon Clark, an unarmed black man killed in his own backyard. Omalu’s work confirmed that Clark was shot in the back six times by Sacramento police.

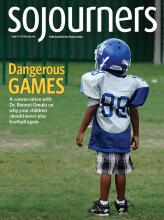

Omalu is best known, however, for the startling discovery he made after performing an autopsy on former NFL player Mike Webster. As chronicled in the 2015 film Concussion, with Will Smith starring as Omalu, the then-medical examiner in Pittsburgh found Webster had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head—the kind of blows to the head you ought to expect when playing tackle football.

But despite his daily proximity to death, Omalu, a committed Catholic, has nothing but gratitude. “I am blessed because I encounter death every day ... I came to the world naked, cold, and lonely, and I will leave the world alone, cold, and lonely,” he explains. “When you realize that, you begin to think of powers, realities, dimensions that are beyond you.”

Omalu is precise and careful with his words. When he says, “I let the Spirit of God percolate into my being,” I half expect to hear his celestial brew bubble. “Everything I do, I do through the eyes of faith.”

Omalu doesn’t seem to be exaggerating; his Christian beliefs and morals permeate his outlook on everything. Early in our conversation, he asks if I’m a Christian writer, and I try to say I’m more like a Christian who writes, but Omalu isn’t one to thread the needle between competing postmodern definitions of Christian vocation. The Bible on his desk is as important to him as any medical textbook—and based on its proximity to his laptop, he might use the Bible more often.

And it’s with this same precision that Omalu offers an uncompromising assessment of the sport running U.S. recreational life each Saturday and Sunday (plus Monday nights on ESPN, Fridays if you’re in high school, and it’s even trying to make Thursdays a thing) for about six months out of the year.

Read the Full Article