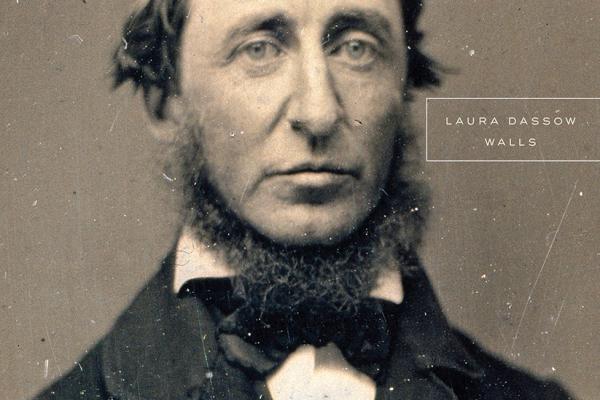

EVEN AFTER 200 years, Henry David Thoreau continues to be a controversial (and, to some, annoying) figure. In a 2015 New Yorker article titled “Pond Scum,” Kathryn Schulz eviscerates the 19th century author of Walden, describing him as “self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self control.”

Schulz is not alone in her criticism. In Thoreau’s own beloved village of Concord, Mass., he was attacked for being a hypocrite because he would slip away from his hand-built cabin in the woods to enjoy hot meals and drop off his laundry at the family home. This after he had brazenly declared himself self-sufficient. To make matters worse, he thundered against alcohol, gluttony, and sex in Walden, just as many were happily putting Puritanism behind them.

Yet Thoreau not only endures but is thriving in today’s 21st century zeitgeist. He has “come down to us in ice, chilled into a misanthrope prickly with spines,” declares Laura Dassow Walls, author of a recently released biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life.

Walls writes of Thoreau set in a New England deep in the throes of change. Ever mindful of the worrisome new global economy, Thoreau sought out and wrote about those being left out and struggling. His subjects included Native Americans, Irish immigrants, and ex-slaves, who were living precarious lives along Walden Pond. Perhaps his interest stemmed from the fact that, for years, Thoreau’s own extended family lived a life of penury, according to Walls, before the small pencil factory they ran in their backyard prospered, making them comfortable during Thoreau’s adult years.

Read the Full Article