Nov 2, 2016

Even by this pope’s standards it was a bold move.

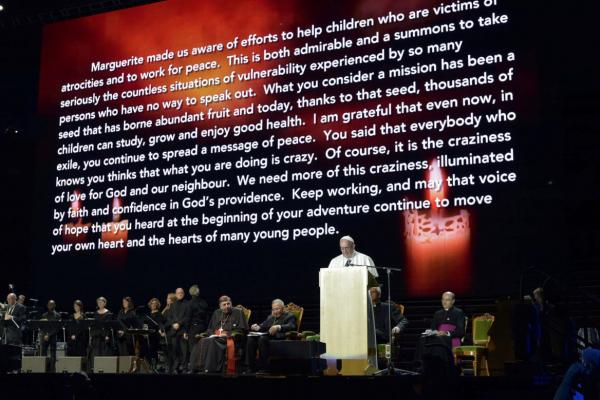

Francis, the spiritual leader of more than a billion Roman Catholics across the globe, this week traveled to Sweden, one of the most secularized countries in Europe, to take part in events marking 500 years since Martin Luther kickstarted the Protestant Reformation.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login