Feb 23, 2016

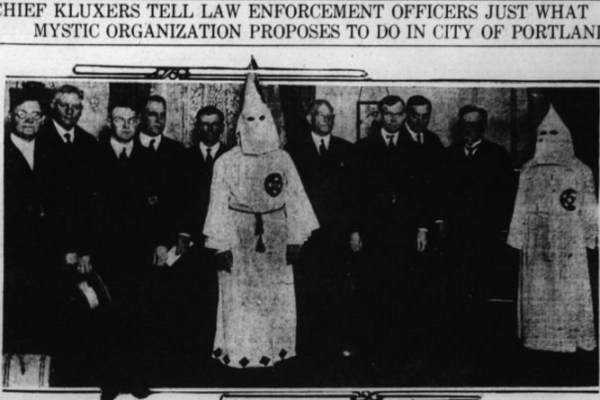

Did you know that Oregon was founded as place for white people only?

Yes. Yes, it was.

In a complicated twisting political tale of pre-Civil War American history, enshrined in my state’s constitution were explicit and clear black exclusion laws.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login