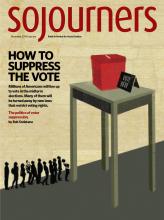

IN THIS YEAR'S midterm elections, hundreds of thousands of Americans will have a much more difficult time casting their ballots than they did two years ago. And it won’t be because of rain, or early winter snows, or other acts of God.

It will be because powerful people don’t want them to vote.

Why? They stand to gain politically if the “wrong” people can be kept away from the polls. It’s the opposite of a “get out the vote” campaign—“keep out the vote” describes it better.

The tradition of keeping particular sectors of the population from taking part in the franchise goes back to the founding fathers. John Adams, for instance, believed that only rich, successful, smart people should vote—and only people of a certain race and gender, of course.

“Such is the frailty of the human heart,” Adams wrote in May 1776, “that very few men who have no property have any judgment of their own.” At the time, politicians in Massachusetts wanted to allow men who didn’t own property to vote. Adams thought that was a bad idea. For him, no property meant no vote.

Read the Full Article