The Pantex plant in Amarillo, Texas, is the end of the line for the assembly of all U.S. nuclear weapons. Parts of nuclear warheads are shipped from all over the United States to Pantex, where they undergo final assembly.

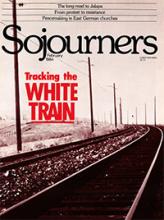

The Trident submarine base at Bangor, Washington, is the end of the line for the deployment of a number of those weapons. Every three to five months the heavily armored White Train winds its way north from Pantex to Bangor to deliver approximately 200 more nuclear warheads to the Trident base.

The Catholic bishops of the two dioceses in which Pantex and Bangor are located, Amarillo Bishop Leroy Matthiesen and Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, help provide a nonviolent counterforce to the Pantex-Bangor connection.

On June 12, 1981, Hunthausen announced his support for widespread tax resistance, an action he has personally taken, as a nonviolent way to halt the arms race. The most widely quoted statement in his speech was: "I say with a deep consciousness of these words that Trident is the Auschwitz of Puget Sound."

Read the Full Article