Desmond Tutu is a small man with a big laugh. He is nothing less than effervescent, eyes sparkling behind gold spectacles, hands gesturing energetically. He bounces into rooms like an elf, projecting an aura of joy that at once puts others at ease and rivets their attention.

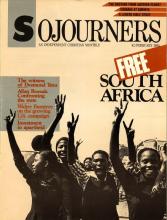

It is this black South African, whose charm and spirited manner are downright disarming, who recently was awarded the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize. Millions around the world have since come to admire and appreciate this delightful man.

Yet his very merriment threatens some of the most powerful men in the world—not only the white rulers of South Africa, but also corporate magnates and even President Reagan, who graciously invited Tutu to meet with him at the White House after the Anglican bishop had, in public, all but dared him to do so.

Tutu has a gift of "speaking truth to power," and he draws his courage from spending several hours in prayer each day. His commitment and integrity are fruits of his deep love for God and his people. He is motivated by a finely tuned sense of the injustice of the world, and he is haunted by the memory of a young black South African girl who told him she drank water to fill her stomach.

No treatment of the South Africa issue could be complete without a portrait of this extremely influential man. Those who oppose Tutu and his causes call him dangerous and subversive. Those who know him call him a man of God. He is head of the South African Council of Churches and recently was installed as archbishop of the Anglican Church in Johannesburg, South Africa.

What we offer in this issue are only brief glimpses of Desmond Tutu—the Christian, the Nobel laureate, the newsmaker, the preacher.

The item presented here contains excerpts from a press conference Tutu held at the Washington Cathedral in Washington, D.C., on December 23, 1984.

Read the Full Article