Why is an ecumenical magazine paying so much attention to the founding of a Catholic religious order? What do the life, message, and legacy of a Spaniard born 500 years ago have to say to us today?

Plenty, as the accompanying articles illustrate. What is important to us here is not just the history of the Jesuits but the basic central insights on the spiritual life that Ignatius and his followers have left us.

Ignatius of Loyola established an approach to spirituality that has proven helpful to Christians through the centuries -- and continues to be a fertile ground for prayer and discipleship today. The impact of this spiritual teaching has gone far beyond the Catholic Church, with good reason.

As Christians today seek to enrich their own lives in the Spirit, more and more people are finding themselves drawn to women and men in the church's history who serve as guides for the journey. These pathfinders -- the "classics" of Christian spirituality -- help us to see more clearly our own way along the journey of faith. -- The Editors

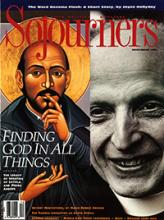

Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the largest Catholic religious order, the Jesuits, has been attracting widespread attention this year, the 500th anniversary of his birth. Ignatius' legacy goes far beyond the founding of the Jesuits -- he launched a distinctive style and tradition of spirituality that is particularly apt for our time.

Read the Full Article