Apr 30, 2015

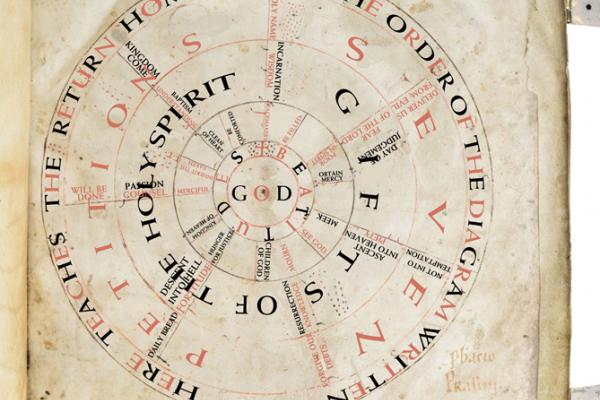

If much of life in the High Middle Ages seems foreign to us, the detailed workings of the wheel — along with four others like it that have survived to the present — are a real riddle.

Schematic prayer guides were more common in later centuries, said Lauren Mancia, a medievalist at Brooklyn College who has examined the Liesborn Wheel.

“Monks and nuns in the Central Middle Ages often get a bad rap for unsystematic thinking — doing all this prayer by rote, mumbling, and not caring about the sense,” said Mancia.

“This diagram suggests that they’re not just mumbling, they’re using a mnemonic device to remember and internalize, or even to make an inner journey.”

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login