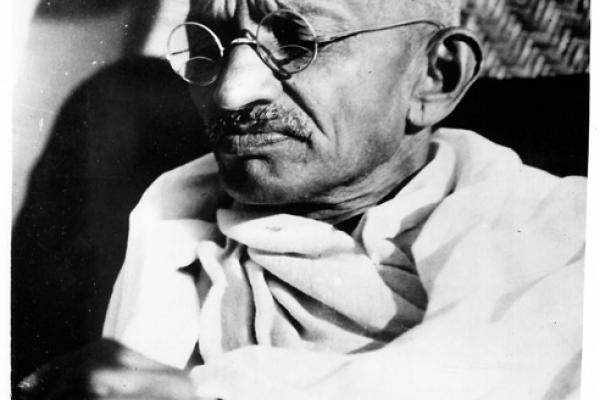

Mention the concept of “nonviolent resistance” and two names immediately come to mind: Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian leader who led his nation to independence from British colonial rule, and Martin Luther King Jr., who led the struggle for civil rights in America. Tragically, both champions of nonviolence were assassinated: Gandhi in 1948 and King 20 years later. Today many people throughout the world revere both advocates of nonviolence.

While Gandhi and King were largely successful in their efforts, the question remains whether nonviolent resistance is always the most effective strategy in the face of radical evil, injustice, and aggression. After all, there remains a thin line between nonviolence and martyrdom.

Professor Charles DiSalvo of West Virginia University has recently published “M.K. Gandhi, Attorney at Law: The Man Before the Mahatma,” an excellent study of Gandhi’s 20 years as a young attorney in South Africa where he faced anti-Indian stereotyping and bigotry.

Interestingly, Gandhi’s two closest friends were Jews he knew in Durban and Johannesburg. But despite Gandhi’s personal friendships and his commitment to freedom and security for his own people, he was indifferent, at best, or naive, about the Nazi persecution of Jews.

Read the Full Article