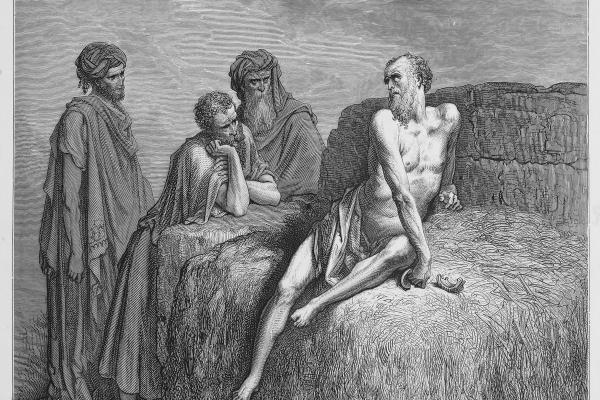

The world of Christian theology has seen its fair share of writings that address horrible suffering and the confusion about God’s character that it causes. The question has been on my mind in light of the Philippines’ calamity. Although satisfying answers are difficult to come by with a topic like this, I offer a few insights that have helped me to continue to trust God’s love. The biblical character of Job shows us how, as believers in a loving God, we should regard and respond to suffering around us.

It no longer surprises me when I hear people express cynicism and doubt about a caring God — I sometimes wonder why more Christians have not done so. Whose faith can remain undisturbed when Typhoon Haiyan kills 5,000 Filipinos and inflicts misery on thousands more? I recall a photo of a woman weeping by her child’s body inside a damaged church. Who can imagine her despair? Can we conceive of the hell endured in the same region by enslaved women and girls who are raped and degraded every day, every hour?

Read the Full Article