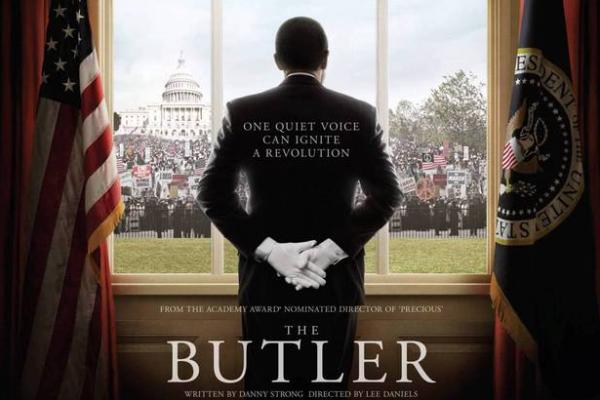

As people stepped on our toes and stood anxiously in front of us, waiting to exit the crowded theater, three of us sat weeping at the close of Lee Daniels’ The Butler. Even now, as I recall that moment, it brings tears to my eyes.

How do I describe the movie? Utterly intense. Remarkable. Heartbreaking. Inspiring. A genius capturing of the complexities of the Civil Rights Movement, of the history of race in America in the 20th and early 21st centuries, of presidential decision making, and of family.

I sat next to my colleague, Lisa Sharon Harper, who sobbed at the violence, tragedy, and passionate courage displayed on screen. It was a challenge. To be a white woman sitting next to an African-American woman as she wept over the suffering of her people — often at the hands of my people. It was neither her nor I who had perpetrated these specific acts, but we are certainly still caught in the tangled web of systemic racism and the histories that our ancestors have wrought us.

Even as we had waited in the theater prior to the movie's start, we spoke of serious subjects. She shared some of her lineage and the challenges of legal records that simply do not exist when ancestors are slaves or perhaps a Cherokee Indian who escaped the Trail of Tears in Kentucky and suddenly appears on the U.S. Census in 1850 as an adult. We spoke of her leadership in the church, and I encouraged her to continue speaking even though she is one of the lone women who graces the stages in front of national audiences. I told her, "You must do this so that other women who come after you can do this. You must do this for women right now. You must do this so that I can do this." We bonded over being women in ministry.

And then the separation came. I do not know Lisa's shoes — the road that she walks due to the color of her skin. I see her in all of her glory — passion, intelligence, creativity — and not in all of her blackness. Our world sees her with racial eyes.

The Butler's brilliance lies in its multi-level approach. As someone trained to remain invisible in any room, the domestic help is privy to private conversations between the president and his aids. Cecil Gaines, our protagonist, first encounters President Eisenhower, who is faced with integration in Little Rock, Ark. As Eisenhower sits painting, he asks Cecil if he has any children and if they go to an all-black school. Cecil replies politely but has been trained to remain as silent as possible. The audience is left to wonder if his few words will amount to anything.

Other presidents begin to ask more questions of him. They cannot help but notice that he is a black man. We greet a Nixon who is campaigning to be president when he stops by the kitchen to pin them with campaign buttons and takes a moment to ask them what they, as representatives of the African-American race, most want.

There is a scene where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., casually remarks about how valuable domestic servants have been in racial reconciliation. The close relationships, though sometimes with few exchanges or depth, have an effect on the white people being served. I was struck by how King called it subversive. The whites saw the humanity of the blacks without even trying. It was an incarnational environment — intended as a hierarchy of submission — that unknowingly cultivated understanding, tenderness, and recognition. It seems that we cannot help but be changed by those around us.

At home, Cecil has raised two sons. The oldest quietly works hard and graduates from high school. Rather than attending the nearby Howard University, he enrolls at Fisk University where it seems that his determined plan begins to unfold. He goes to Jim Lawson's "Love" meetings and attends in training for withstanding the violence that will certainly be hurled at him during their lunch counter sit-ins. He has come to be a spark in the Civil Rights Movement.

If Cecil is committed whole-heartedly to serve at the pleasure of the president, then Louis Gaines, his oldest son, is committed just as equally to serve at the displeasure of the status quo. He begins to be beaten regularly and arrested over a dozen times.

One of the most frightening scenes of the movie is when Louis is traveling on a bus with other students in the Civil Rights Movement and they encounter the Ku Klux Klan with fiery torches who surround the bus. As I remembered some of my American history and knew that people would die in this encounter, I gripped the arm rests as tears filled my eyes. So much hate and fear filled the screen. Just kids. Kids trying to sit next to each other at the lunch counter. Kids trying to make an honest living. Kids tired of being told that they couldn't.

Cecil pleads with his son to stop doing this. "I am making an honest living to pay your way through college so that you can have a better life!" he exclaims. Yet Louis knows that no matter how much education he attains, there will always be barriers in their country if he does not work to actively change them. He continues to be beaten and to protest because he believes that it will bring about change. Cecil continues to serve and to be silent because his belief is as equally fervent.

I wonder how much their upbringing has influenced their actions. Certainly children are instilled with many values by their parents. Somehow, Cecil has encouraged Louis to rise up and protest, even though Cecil begins to separate himself further and further from his flesh and blood, no longer taking his phone calls.

The tension exists over how to bring change. The tension exists over whether it is even possible to bring change. The tension nearly tears the family apart.

We see the tolls that have been taken. The silent posturing of Cecil’s family against itself. The cost of the toll in his life. In Cecil's childhood, he lived in a violent and turbulent world that directly wounded him. Through submission and hard work, he attained safety and a measure of prosperity for his family. In his eyes, he had overcome. To Louis, there was still so much more ground to cover. Through a series of national actions that his son participates in, Cecil continues to endure violence and loss, this time due to the speaking and resistance that his son enacts. In the end, is there a way for this man to win? Can any course of action bring him to greater joy, peace, or wholeness?

My eyes are continually covered by the veil of white privilege. I must constantly tear it away and see the world as it is, not as I have enjoyed it. Even now, I hope to honor Lisa with my words to describe what seems more her story than mine. Yet, it is both of our stories. We are both entangled in the web of human history and have the ability to affect the threads that are woven.

I am clinging to the hope that our work — done together at Sojourners — might be making a difference. That the same spirit that the Civil Rights Movement possessed, which plays center stage in The Butler and sparked Sojourners' beginnings, continues to drive our movement — that we are committed to racial reconciliation and to bringing about justice in socioeconomic ways through public policy changes. Are we doing enough? Am I part of the solution, rather than simply a bystander who perpetuates the problem?

Am I honoring my friend? Am I honoring my neighbors? Am I honoring our collective ancestors — the many who gave their blood and their lives to bring about justice and true freedom in the United States? I pray that I am, and I know that I must keep praying because there are so many ways that I am not.

Go see Lee Daniels’ The Butler. Be changed by the realities. Offer your heart to our history and the hope for our future. Catch the courage of the Freedom Riders as well as the domestic servants. Let them inspire you to be subversive in your own community.

Stacey Schwenker is Advertising Associate for Sojourners.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!