Jul 24, 2013

The 35-acre campus is an island of young people, where teens and 20-somethings outnumber grownups by 10-to-1.

The place is awash in fresh-faced students, and even the workers — from the cafeteria to the copy center, the mailroom to the bookstore — and most of the teachers are under 30.

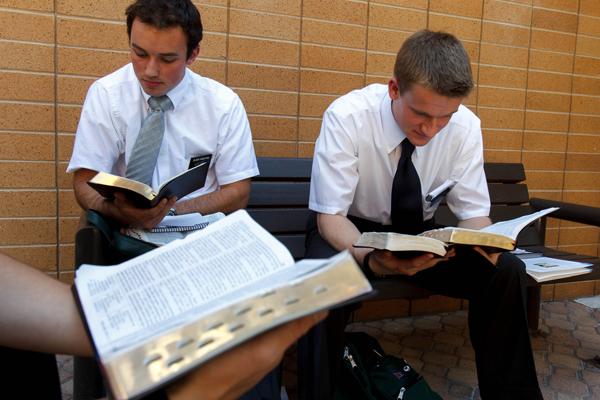

It’s no “Animal House,” though, with raucous frats, food fights, and binge drinking. This is Mormonism’s elite Missionary Training Center, where the men wear white shirts and ties, the women don modest skirts and dresses and everyone is expected to heed the rules.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login