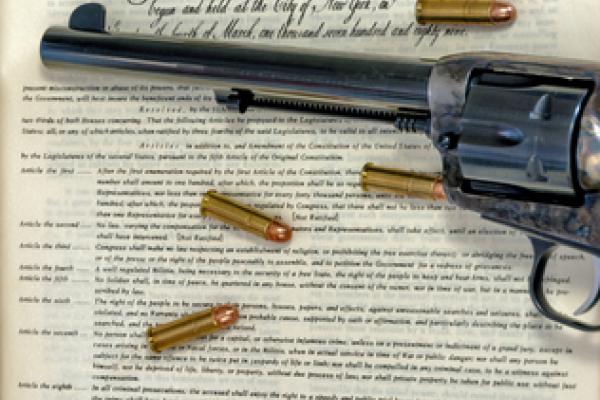

How did this gun-owner-since-he-was-eight find himself at a prayer vigil to end gun violence on the steps of the Michigan state capitol? The easy answer is that Michigan Prophetic Voices, a nonpartisan, statewide organizing clergy group invited me to be there. But I had another reason.

In my family owning a gun was explained as a rite of passage, not as a Second Amendment right. When my father handed me my first gun he said, "You are old enough now to learn how to use this safely. There is one thing you have to promise me: never point it at anyone. If you do, I will take it away for good." I made the promise.

The man who said those words had heard different words from his father. "Never steal another man's property," my grandfather had told my dad, "and if it's yours, you fight like hell to keep it."

Those words shaped events of an early August morning in the 1970s when both of those men leveled shotguns at would-be burglars in the family business and, out of fear for their own lives, fired. One of those 20-something men was killed.

Read the Full Article