Suppose there are two inmates convicted of similar crimes. Both appear to be equally contrite and rehabilitated. One is black, the other white. The white one gets pardoned by the governor, the black one does not. Is this fair?

What if one was rich, the other poor? If one had political donors for friends, but not the other? And what if most of those pardoned by this same governor were white, rich, politically connected, or they were convicted of quite violent crimes?

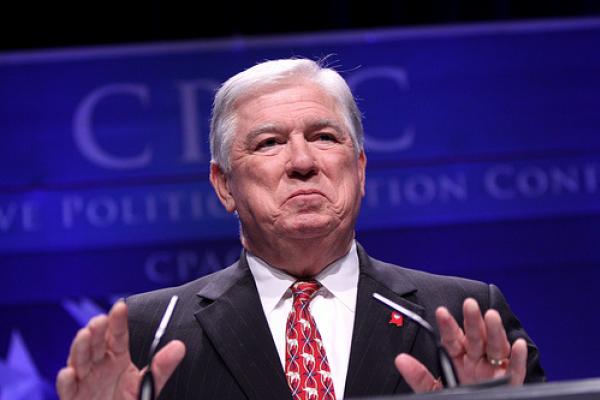

Judging by the reactions to former Governor Haley Barbour's granting pardons or clemency to 200 or so felons on his last day as governor of Mississippi in January 2012, this seem to be the point at which many raise their hands, asking, "what is going on here?"

To my eyes, Gov. Barbour unfairly (and illegally?) predetermined who was eligible to be pardoned based upon their professing the adoption of his religion.

Read the Full Article