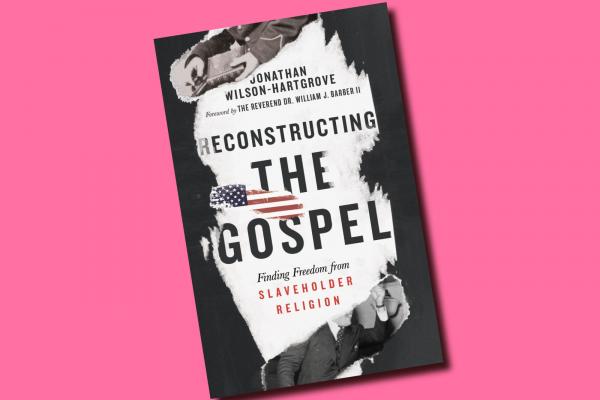

FALSE GOSPEL is interwoven throughout both our national identity and theological imagination. In Reconstructing the Gospel, Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove excavates our common story alongside his own lineage. With thorough historical analysis, Wilson-Hartgrove confronts misguided narratives of “who we are” and illumines our current sociopolitical reality.

Beginning with America’s original sin of slavery, Wilson-Hartgrove moves through the Reconstruction era and subsequent redemption struggle, the Jim Crow South, the civil rights movement, and finally, to the truth of today: Systems of enslavement aren’t gone, they’ve merely evolved into new forms. Along the way, Wilson-Hartgrove highlights those who have baptized the sin of racism—from missionaries on slave ships to slavery-supporting preachers Thornton Stringfellow and George Washington Freeman and to Franklin Graham and the Moral Majority—and outlines the destructive patterns of racial blindness, racial habits, and racial politics.

Wilson-Hartgrove reveals that he is “a child of Klan country,” an heir to the sickness of racism. “A man torn in two,” he writes, divided between what Frederick Douglas described as the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ. Reconstructing the Gospel tells of his own untethering from slaveholder religion.

In perhaps the most compelling chapter, titled “Living in Skin,” Wilson-Hartgrove examines how this tradition affects white folks’ dis-ease with embodied life. He asks, “What evil spirit has left us out of touch with our bodies?” Believing the myth of white supremacy requires relinquishing full humanity. “You can’t shut up compassion in a human heart one minute and then go back to normal the next,” says Wilson-Hartgrove. In the process, white folk lose sight of their bodies and solely elevate the spirit. A disconnected body and spirit results in a “fail[ure] to connect faith and politics in meaningful, consistent ways.”

Read the Full Article