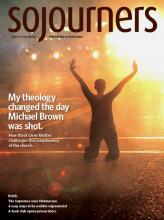

AUG. 9, 2014, is a day I’ll never forget. It was the day that Michael Brown was killed by Ferguson, Mo. police officer Darren Wilson.

For many young people in the United States, especially those of us involved in the Black Lives Matter movement, this was our Sept. 11. We all remember exactly where we were and what we were doing when the news broke of another police-involved killing of an unarmed black citizen.

I was in the final days of a yearlong internship with Sojourners. My fellow interns and I were on our closing retreat in West Virginia. I was on my phone checking my Twitter timeline when I began to see retweets of images: Michael Brown laid out on Canfield Drive with blood still leaking from his bullet wounds. I remember the anger that instantly came over me. “Not another one!” was all I could think.

As the day wore on, I felt frustrated that I was stuck in a retreat house, forced to sit idly by while the grieving community in Ferguson was antagonized by officers in riot gear with police dogs. I knew then that I had to do whatever it would take to join the people in this fight for justice. I never imagined how this movement would change the way I—and many others—actually do theology.

Read the Full Article