MY JOURNEY WITH the Uyghur people began in 1985 when I accepted a teaching position at Xinjiang University in Urumqi, a regional capital on China’s far western border. My wife and I made many friends during our seven years there. The Uyghur, an ethnic Turkic people of 12 million, are predominantly Muslim and live in the only Muslim-majority area in China, called the Xinjiang Uyghur Au-tonomous Region (by China) or East Turkestan (by the Uyghur and Kazakh peoples).

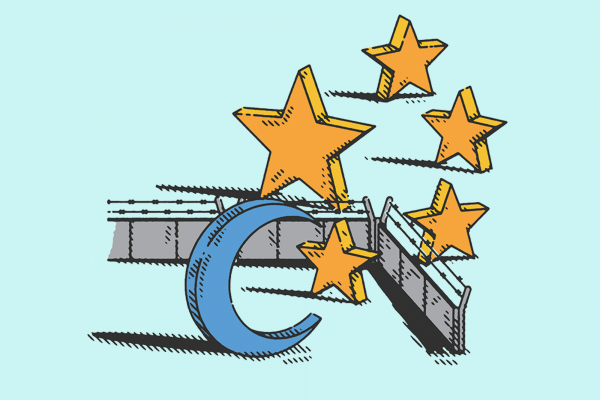

In 2017, we were greatly distressed to hear credible reports that the Chinese government was interning citizens in (what the government calls) “reeducation” camps. As many as a million people have been detained in 300 to 400 facilities in Xinjiang prov-ince, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, including “political education” camps (part of a 70-year program of forced cultural assimilation), pretrial detention centers, and prisons. Detainees are subjected to torture, cultural and political in-doctrination, and forced labor. The U.S. Holocaust Museum says this state-sponsored violence meets the threshold for genocide and crimes against humanity. Friends and colleagues have disappeared.

In May, I met Uyghur poet, linguist, and human rights activist Abduweli Ayup on a Zoom call. Ayup spent 15 months in Chinese prisons for his defense of Uyghur linguistic culture. On our call, he told the terrible story of his failure to save from the camps his 30-year-old niece, Mihriay, who taught Uyghur children in the Chinese education system.

Read the Full Article