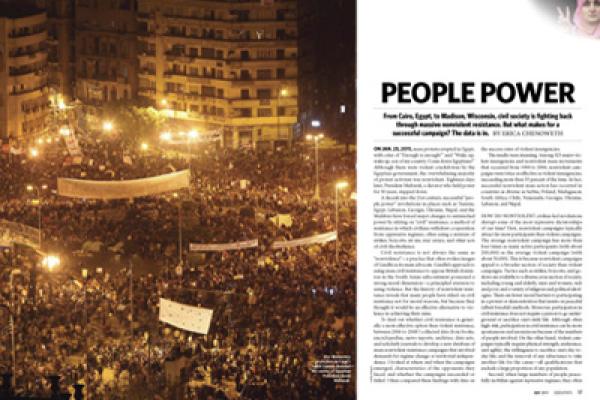

On Jan. 25, 2011, mass protests erupted in Egypt, with cries of "Enough is enough!" and "Wake up, wake up, son of my country. Come down Egyptians!" Although there were violent crackdowns by the Egyptian government, the overwhelming majority of protest activism was nonviolent. Eighteen days later, President Mubarak, a dictator who held power for 30 years, stepped down.

A decade into the 21st century, successful "people power" revolutions in places such as Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Georgia, Ukraine, Nepal, and the Maldives have forced major changes to entrenched power by relying on "civil" resistance, a method of resistance in which civilians withdraw cooperation from oppressive regimes, often using a mixture of strikes, boycotts, sit-ins, stay-aways, and other acts of civil disobedience.

Civil resistance is not always the same as "nonviolence" -- a practice that often evokes images of Gandhi as its main advocate. Gandhi's approach to using mass civil resistance to oppose British dominion in the South Asian subcontinent possessed a strong moral dimension -- a principled aversion to using violence. But the history of nonviolent resistance reveals that many people have relied on civil resistance not for moral reasons, but because they thought it would be an effective alternative to violence in achieving their aims.

To find out whether civil resistance is generally a more effective option than violent resistance, between 2006 to 2008 I collected data from books, encyclopedias, news reports, archives, data sets, and scholarly journals to develop a new database of mass nonviolent resistance campaigns that involved demands for regime change or territorial independence. I looked at where and when the campaigns emerged, characteristics of the opponents they faced, and whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. I then compared these findings with data on the success rates of violent insurgencies.

Read the Full Article