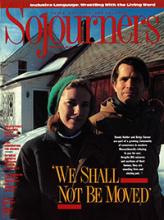

IT'S A WINTER SATURDAY MORNING like many others in western Massachusetts. The snow outside is deep, but the sun beats in through the picture window and warms the dining room, aided by the heat of a wood-burning stove. Betsy Corner serves ginger tea and keeps plates heaped high with hot pancakes, topped with canned peaches that came from the trees in the yard in a warmer season. Her husband, Randy Kehler, is battling the flu. Their 10-year-old daughter, Lillian, eats quickly and takes off on her bike to see the lamb just born on the neighboring property.

It is January 20, 1990. If there is any fear or apprehension here, it isn't perceptible. But, as of midnight the night before, Betsy, Randy, and Lillian could be put out of their home at any moment.

They live in Colrain, Massachusetts (population 1,595). The town is tucked in a valley spread with apple orchards and maple trees, tapped this time of year for their sweet sap. A cluster of a few dozen homes at Colrain's center is marked by a diamond-shaped, yellow road sign proclaiming "THICKLY SETTLED."

The homes are mostly clapboard, and all three of Colrain's churches have standard New England-fare white steeples. Among the town's residents are many hard-working laborers and a few artists, trustworthy dairy farmers "in the best of the Old Yankee tradition" (according to Randy) and -- during the summer -- Richard Nixon's former ambassador to South Vietnam (owner of the only tennis courts in Colrain).

A cotton mill that specialized in hospital bandages stands silent, its business moved south. An old covered bridge crosses the frozen North River, and a small graveyard on the side of Colrain Mountain has headstones dating back to the mid-1700s.

Read the Full Article