Dr. Charles H. King is founder and president of the Urban Crisis Center in Atlanta, now in its twelfth year. Its main goal is to bring about racial understanding and equal opportunity by sensitizing white institutions to the reality of racism.

King is a Baptist pastor who served 10 years at Liberty Baptist Church in Evansville, Indiana. He now conducts seminars on race relations that bring whites and blacks together to confront their racial attitudes and encourage changes leading to racial reconciliation. The following interview was conducted for Sojourners in March, 1981, by Kathy Maxwell, an evaluation coordinator for the Atlanta Cities and Schools Project and a longtime friend of King.--The Editors

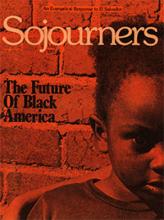

Kathy Maxwell: Dr. King, you have spoken before on black survival in the '80s. The topic of this interview is the future of blacks in America. This seems to be a different perspective.

Charles King: No. The future of blacks in America actually is a matter of survival. It's not just a matter of what blacks will do; the real question is what whites will do about the problems of blacks in the future. Our entire destiny is tied up with the nature of how white society reacts to those problems.

And I detect among most blacks a sense of despair, of anger--not outwardly expressed anger, but an inner hostility, particularly among young blacks in colleges and universities who are looking at the institutionalized operations of white systems that will not allow blacks to exist within them. These young blacks are turning again to black unity and seeking survival within the concept of blackness. And I consider that a one-way street--and suicidal.

Read the Full Article