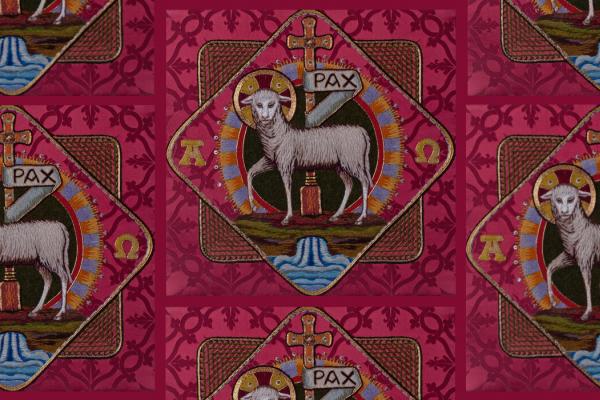

WHEN I ASKED various Christians about their reaction to the book of Revelation, I heard back: “Dark and scary.” “It’s too violent for me.” and “It’s a total blank. I really don’t know anything about it.”

But this dramatic, political, incendiary scripture is important for us to understand today. It was written in empire and should be read today in our own imperial context to learn what it means to follow the Lamb. We also need to know how it has been used and misused by Christians throughout history. As evangelical New Testament scholar Gordon Fee says, “To understand what a text means, we must first understand what it meant!”

Reading the apocalypse

First, a bit of background. The word “revelation” (apokalupsis in Greek) belongs to a popular genre of Jewish literature prevalent from about 250 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. An apocalypse purports to be a vision of a realm beyond our normal senses, where God is in control and will eventually break in to rescue the faithful from oppression. Apocalyptic literature is intended to bring hope during times of political uncertainty or persecution.

The books of Daniel and Revelation are our only canonical examples of apocalyptic literature. Other Jewish apocalypses written during this period are attributed to heroes of old, such as Adam, Enoch, and Abraham, to lend authority. Daniel also is pseudonymous, since Daniel lived 400 years before the second-century B.C.E. events described in chapters 7 to 12 of that book.

Only John in Revelation uses his own name and his own location: “I, John, your brother who shares with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom and the patient endurance, was on the island called Patmos because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (1:9). He is in political exile on Patmos, off the coast of Asia Minor (now Turkey), because of his witness to the good news of Jesus.

Read the Full Article