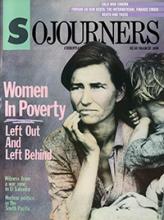

The faces of the unemployed beamed into our living rooms and etched into our mind's eye are often wearing hard hats and have neglected beards. That is to say, they are men. We know that they are having to bear the grief that comes from the loss of income, change in identity, and deterioration of hope. But the grief and psychic rearrangement that result from unemployment are not the exclusive domain of men.

There are other faces, less often shown: faces of the wives and children of the provider who can no longer provide, and faces of working women, married and single, whose own pink slip has meant much more than the loss of "pin money." In many ways their experience of unemployment is similar to that of men, their grief shared. In other ways it is unique to women.

Clara, a coal miner's wife, remembers vividly the day her husband was laid off:

It was a day to remember, I'll tell ya. I kept telling him, "I heard these rumors. They're gonna close the mine."

He says, "Never! They keep sayin' there's 10 years left, there's 20 years left."

I says, "Mick, there's rumors."

He says, "Don't believe them."

So [when] it came across the news, I went hysterical. Y'know, you figure you go from like $100 a day to--what was it then--$182 a week on unemployment. I panicked. The whole bottom drops out.

When "the bottom drops out," the wives in working-class families go through their own experience of grief. But their loss is different; their disillusionment is related to the illusion attached to growing up female in America.

Read the Full Article