Here it was May 4, 1970, hardly two days after the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the slayings at Kent State, and I was organizing the student strike at Hamilton College, participating along with my contemporaries in hundreds of colleges and universities across the United States in the “great catharsis” of ‘70, the last big blowout of the Peace Movement. It was a glorious spring week as I recall, and the time seemed preordained, perfect for a successful revolution as we marched, protested, mobilized, and painted arm- bands while the Rolling Stones sang “Street Fighting Man” in the background.

Yet it was less than cathartic for me. No longer a student (having graduated from Hamilton nearly a year before) and no longer employed (having quit my job at the Reader’s Digest six weeks previously) I found the constant activity to be as unsatisfying as it was compulsive. Concessions won from anxious college administrators seemed empty to me in my position between two worlds, and the best of our efforts merely an exercise in futility. So it was that I lived through that week with an uncomfortable sense of the ambiguity of my own situation, an anxiety born of double-edged alienation.

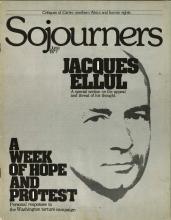

On the advice of a professor, I walked into chapel one evening during those days in time to hear the following words spoken softly yet forcefully: “If, say about the end of the decade, there be any survivors of the death of American culture, and should any of them be theological literates, and, if, while sifting the rubbish, they happen upon a book or two by Jacques Ellul, they will surely be mystified as to why a message so intelligent and urgent was not more heeded.”

Read the Full Article