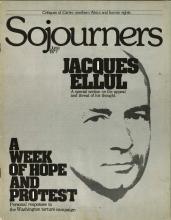

I first read Jacques Ellul’s False Presence of the Kingdom and Hope in Time of Abandonment (both published by Seabury Press) while riding a Greyhound from Boston to Atlanta in the late spring of 1973. Although Ellul is not what one would call a great prose stylist, I plowed through the two volumes as if they were racy novels, letting the tiny reading lamp above the seat burn late into the night until my eyelids drooped in rhythm with the motion of the bus. By the time we reached the Georgia line, I had finished both.

What kept me glued to the pages was the fact that in these books Ellul presented a critique of religiously based political activism which articulated, made sense of, and expanded the feelings and thoughts I had dwelt upon for some time. This critique, if I can attempt to sum up its major points in a few phrases, argued that most such activism ended in faithless conformity to the world, a conformity which robbed the gospel of its identity and power.

Most such efforts, moreover, were characterized by an embarrassing combination of incompetence and irresponsibility on the part of Christian participants. At their worst, these activist efforts became the tools of demonic forces and movements; even at their best, they were specimens of what Ellul called “conformity to tomorrow.”

His description of this conformity bears quoting here in full:

Read the Full Article