THERE IS NOTHING new under the sun, as the author of Ecclesiastes reminds us. In this, theologian Elsa Tamez said, we can “find solidarity in our discontent.”

I visited Charlottesville in May, nearly a year after the “summer of hate.” I heard from young Christians who had been on the frontlines at Robert E. Lee Park (now called Emancipation Park). I stood in the presence of their discontent, listening and witnessing to the ongoing, traumatizing effects of last summer’s “fascist lollapalooza,” as one University of Virginia professor put it.

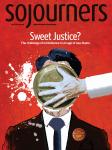

Still reckoning with the memory of Aug. 12, one leader in his 20s shared how he had tried to be a nonviolent defender amid multiple “armed actors,” including the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, anti-fascists, and police. By the end of that day, two state troopers were dead, one woman was murdered, dozens were injured, and the whole community was emotionally, spiritually wounded.

In small towns such as Charlottesville and more recently Coweta County, Ga., fascists are organizing cadres of white supremacists, neo-Confederates, neo-Nazis, and European identity movements. They are terrorizing small towns in America, especially those with liberal arts colleges. They are intentionally setting up young people in ideological cage fights and goading them to kill each other.

A CENTRAL PROBLEM for the writer of Ecclesiastes is that “no one remembers the former generations, and even those yet to come will not be remembered by those who follow them” (1:11). There is a loss of historical memory. “Collective amnesia means the death of a people,” wrote Tamez.

But to remember requires storytellers who will carry the stories and remember the details. At this year’s Freedom and Liberation Day gathering in Charlottesville, the community gathered to mark the day 153 years ago when Union troops marched into the city and liberated more than half the population. In remarks at the event, Jalane Schmidt, who teaches religious studies at the University of Virginia, provided context for the Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues that were the frontlines last summer.

“Neither of those Confederate generals ever came to Charlottesville, except Stonewall Jackson, who came through in a coffin on the way to his burial in Lexington,” Schmidt said. “Yet these monuments and the decades of Lost Cause [pro-Confederate] textbooks ... have manufactured mistaken memories that have quashed our knowledge of our own local history.” Legend focuses on Jackson as an unstoppable war hero. History brings us back to the fact that the brilliant military tactician for a despicable cause was brought down by friendly fire, then succumbed to pneumonia a week later.

Ecclesiastes reminds us that everything has a season. We in no way reconcile ourselves to the anti-human absurdities of the present. We learn how our present-day battles fit in history. We recall and retell the stories that keep us strong.

“Resist wisely in the face of absurdity,” wrote Tamez. This is the most important message in Ecclesiastes—“how to survive with dignity in a dehumanizing and annihilating reality.”

In Charlottesville, there was a man with beautiful tattoos. On his arms were drawn long-feathered quetzal birds flexed for flight and a jade-colored double-headed serpent. The ancient history of Tenochtitlán was alive on him.

In Charlottesville, there were brave young leaders who have reclaimed an abandoned church. They’re learning the stories of the founding circuit-rider pastor and the first parishioners who sat in its pews. Their worship banners are origami peace cranes and Black Lives Matter posters. Outside, they’ve planted a garden.

In Charlottesville, there is a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to plant and a time to uproot.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!