WHEN DUTCH ARTIST Sarah van Sonsbeeck sees photos of people wrapped in metallic emergency blankets and referred to as “migrants” or “refugees,” she’s disturbed by the way this reduces their humanity. “This abstraction, I feel, is very dangerous,” she says.

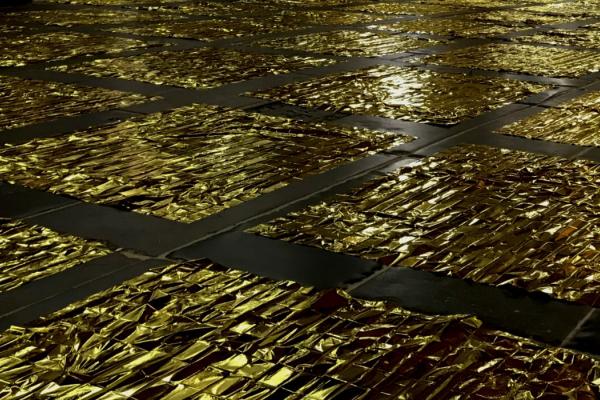

Van Sonsbeeck brought hundreds of gold-and-silver Mylar blankets to Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk (“Old Church”) for a site-specific installation last May to September. The exhibit reflected upon the church’s colonialist history and the ways that Westerners can be unwittingly complicit in migration. The last point troubled the artist from the start of her project.

“As I am not a migrant, am I even entitled to address this?” she asked herself, before realizing she too plays a role. “I belong to and am a product of the Western society the migrants are migrating to,” she says.

Just as Mylar blankets can obscure people’s humanity, van Sonsbeeck’s installation, which evoked ripples in a golden sea when the light hit off the Mylar, covered many of the 2,500 tombstones marking some 10,000 graves that make up the church floor. Some of Amsterdam’s most prominent business people, politicians, and military leaders are buried beneath the 13th century church, and Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh, is another renowned long-term resident.

Tourists hoping to catch glimpses of the city’s remote, entombed past may have been disappointed, but the meditation upon Holland’s present and future was just as powerful. Several works by Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum have involved marbles on gallery floors, one laid out as a map of the world with the expressed aim of having the viewer foot traffic necessarily distort the map; van Sonsbeeck’s Oude Kerk installation accomplished the same thing. As visitors navigated around the Mylar, the golden blankets rustled and moved, sometimes folding themselves over and revealing their silver undersides. Other times they crinkled up. The blankets looked like they were alive and breathing, which made it all the more poignant when the work was “destroyed” and reshaped by inadvertent visitor interaction.

The Mylar, in addition to its use during emergencies, carries other symbolism for van Sonsbeeck. The blankets’ golden hue, she says, references the value, holiness, and light to which society aspires. And the ocean-like effect the blankets created relates to the church’s roots, as many of the bodies buried beneath its floor were sailors, who thought they were doing God’s work as they colonized the new world.

Oude Kerk, which sits within Amsterdam’s Red Light District, used to be one of the city’s few public, covered places where people could mend sails and nets, and naval heroes were buried there, according to the church website. “The barrel vaulting was also fabricated like the inverted hull of a ship using shipbuilding techniques,” the site adds. “And it is not for nothing that the main section of the church is traditionally known in Dutch as the ‘schip,’ or nave. In the church there are actually fragments of paintings that feature motifs found on sailors’ tattoos.”

These sailors of yore, however, had “a very problematic and often horrifically cruel relation to ‘saving,’” van Sonsbeeck says. And beyond this church, which was devoted in the 14th century to the patron saint of sailors and became Protestant in 1578 following the Reformation, van Sonsbeeck sees a broader “complex and problematic relation” that religion has had to “salvation.” “It involves a hierarchy, making the one who is saved dependent on the rules, beliefs, and mercy of the savior,” she says. “The savior puts his beliefs and rules above that of the one whom he is ‘saving.’”

An installation like van Sonsbeeck’s, which invites viewers to relate current events to their faith, can deliver particularly pointed critiques, David Brinker, assistant director of St. Louis University’s Museum of Contemporary Religious Art, tells Sojourners.

“Here the artist draws on the history of the building itself and its relation to the community to inform her contemporary work,” Brinker says. “The same work displayed in a gallery might still carry some of the same conceptual meaning, but would be diminished without the relationship to the church building.”

In fact, he says, it’s rare today for religious communities to commission art beyond what they require to furnish houses of worship or for liturgical purposes. “Perhaps congregations might connect with socially engaged artists as a means to reconsider, propose, and embody the tenets and wisdom of their faith traditions in new, provocative, and effective ways,” he says.

The subject of van Sonsbeeck’s work—immigration, migration, and refuge-seeking motifs—have long punctuated sacred stories of all the major world religions.

“These stories and their exegesis bring out the richness and complexity of those human experiences,” Brinker says. “The Exodus of the Israelites, for instance, is not only about seeking liberation from political, social, and economic repression in the face of military threat, but also about survival in alien circumstances, establishing and maintaining a collective sense of identity, and the tension of hoping for welcome in the face of frequent rejection or worse.”

Contemporary religious art, according to Brinker, can anchor the stories and teachings in the present. “The power of a visual representation to shape a person’s response in the very moment the story is recalled is considerable,” he says. “A representation of Joseph, Mary, and Jesus as Syrian refugees could bring together the tradition and the viewer’s current experience in ways that might be forced or clumsy expressed in prose.”

And art can also have the advantage over political speech of being able to pose questions while simultaneously leaving room for viewers to respond with their own questions, according to Brinker. “Genuinely religious or spiritual art is not merely didactic, but generously leaves space for the viewer’s own response,” he says.

And van Sonsbeeck is very respectful of that space for viewers to add their own reflections.

“Some loved the ‘gold’ for shiny selfies; some felt the migration issue was addressed, either praising it or being horrified by it for various reasons; and one American gentleman even thought the church was being reconstructed!” she says. “However, this work has spoken to many people, and for that I feel truly blessed. It’s not often that art evokes so many personal feelings and thoughts, and that is, in the end, what I hoped for.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!