Nearly three years ago, before I founded a race-relations initiative in one of the South's most racially polarized cities, I taped a piece of paper above my desk: "Go after a dream that is destined to fail without divine intervention," reads the quote from Mark Batterson. Racial reconciliation in Memphis, Tennessee -- a city still stained by Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination here 43 years ago -- is easily such a dream.

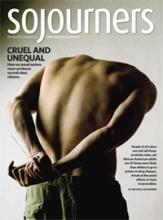

Memphis remains largely two cities -- one black and predominantly poor, and the other white and much less constrained by poverty. Our racial biases and presumptions are part of the fabric of life here -- where we choose to worship, where we decide to live, where we send our children to school, whom we vote for and why. I've had a front-row view to the tensions that shackle and segregate my city.

For the past seven years, I've been the metro columnist for Memphis’ daily newspaper, The Commercial Appeal. I often write about race and how it affects this large Southern city. For the first four years, I frequently found myself engaged in deep race-related email conversations with readers. Generalizations were rampant; white people encouraged me to demystify why black people did what they did, and black people wanted me to chastise white people for slights real and imagined. Literally thousands of emails made this much clear: There was a desire to talk about race and racism, to ask the questions that were pressing but seemed impolite, and a longing to understand and be understood.

I thought: What if this were the city’s conversation, in some sort of safe space? I also thought I was foolish. I’m in my 30s -- what would make me presume I could help fix what had plagued Memphis for longer than I’d been alive?

Read the Full Article