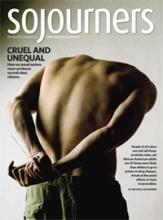

Too many Christians today think about criminal justice in ways that reinforce the human drive to degrade those we punish and to heighten our own sense of superiority. The belief that socially "polluted" people are to be routinely degraded, looked down on, and alienated from law-abiding humanity has deep roots in Western religion. In the Christian theological tradition that undergirds American thought about the penal system, we can see the powerful influence of theological orthodoxies that separate "us" from "them," "saint" from "sinner," "righteous" from "unrighteous," "damned" from "blessed," and "criminals" from "innocents."

For example, Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica, describing the kingdom of heaven, cites Isaiah 66:24, in which "the dead bodies of the people who have rebelled against" God are put on public display as "an abhorrence to all flesh." From Aquinas' point of view, for God’s people to abhor and contrast themselves with the damned is, in fact, part of their blessedness, something that "belongs to the perfection of [the blessed’s] beatitude." The reason? "Everything is known the more for being compared with its contrary, because when contraries are placed beside one another they become more conspicuous." Theologians -- Catholic, Protestant, and otherwise -- too often praise, rather than lament, the idea of Christians getting pleasure by gazing upon the torments of the damned, “lording” it over others in the service of eternal bliss.

And, while they might not admit it, too many Christians in the U.S. today apply the same logic to those the state has marked criminal.

Read the Full Article