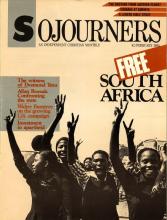

This article is comprised of excerpts from a sermon Desmond Tutu, Nobel peace laureate and archbishop of the Anglican Church in Johannesburg, South Africa, preached at the Washington Cathedral on December 2, 1984.

This service is in thanksgiving to God. I want to add my own thanks to you. We Christians believe that in becoming a Christian you become a member of the body of Christ and part of a worldwide fellowship. You have brothers and sisters scattered over the face of the earth.

We know, too, that we are by our humanity members of the human family and thereby have sisters and brothers in many lands. And we know in our experience what it has meant to be upheld by the love and prayers and the concern of so many around the world. It has been almost a physical sensation, this being borne up by those servant prayers.

Sometimes you may feel sorry for us being in the kind of situation in which we are. Yet I think perhaps the proper attitude ought to be one of envy, for I think it is far easier to be a Christian, a person of belief and faith, in South Africa than it is here. For the issues in South Africa are so obviously clear; you are either for apartheid or against it.

In many respects it has very little to do with personal courage. People say, "Hah! Did you hear what Desmond Tutu said to the government of South Africa? He said to them, 'Hey, when you take on the South African churches, know that you are taking on the church of God. And do you know what has happened to those who have done so in the past? They have bitten the dust, and bitten it ignominiously!'"

No, friend, it has very little to do with personal freedom, personal courage. We are able to witness in South Africa as we do because you are faithful in your witness where you are.

Read the Full Article