'Keep Me Going'

I have a little prayer, my sometimes mantra, "Keep me going, Lord." This little refrain sounded over and over again in my mind and heart as my friend Fern Van Gieson and I hurried down to Wellington, Kansas, 30 miles south of Wichita after receiving the call from Jim Douglass. Jim had alerted us that the train would probably be arriving in Wellington about 7 a.m. We had to check out the tracks and take care of other details, so we were on our way by 4:30 a.m. Thus it was dark and quite chilly, but our anticipation was high. Other women would be waiting at other points. No women on the train, I thought, but plenty alongside the tracks.

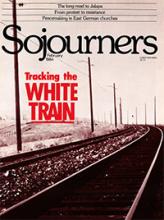

By well after 7 a.m., though, six trains had come and gone. It was very close to 8 a.m., and I knew I should be checking with someone. Just one more train, Fern, then we'll go. And with that the blinking arms came down again, the Santa Fe engines entered the crossing followed by the gleaming, glistening bomb caskets.

We were jubilant, awed, and overwhelmed. I called out the letters and numbers to Fern, who scribbled anxiously and grabbed an occasional quick glance at the cars. Jim Douglass' statement that the train was "bringing Auschwitz to the people" came to mind.

I had seen the ovens at Sachsenhausen, 30 minutes from East Berlin. The ovens were in an out-of-the-way spot on the grounds, and our disarmament tour group had to walk across the compound to see them. I wasn't prepared for my reaction. The casual chatter stopped abruptly as we came upon them. The only sounds in the cold, damp November air were deep breaths and gasps. Low murmurs broke the silence, but no one approached the ovens.

Read the Full Article