THE STATE OF Georgia executed Troy Davis at 10:53 p.m. on a Wednesday in September, by lethal injection. It took him 16 minutes to die. By the next morning there was fresh graffiti scrawled across a wall in my neighborhood: “Troy Davis was murdered.”

Sometimes the very stones cry out.

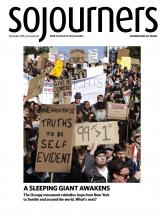

Nearly a million people worldwide signed Amnesty International’s petition urging authorities in Georgia to commute Davis’ death sentence.

Davis spent 20 years—nearly half his life—on death row for a crime it’s doubtful he committed, and the penal system ground inexorably forward. No one could stop it. Not Davis’ family. Not lawyers, protesters, or petition signers. Not the six prison officials who expressed “overwhelming concern that an innocent person could be executed in Georgia.” Not the Georgia governor. Not former president Jimmy Carter, nor William Sessions, director of the FBI under President Reagan. Not even the pope. No one.

Davis addressed his final words to murder victim Mark MacPhail’s family who sat in the front row at the execution. “I know you all are still convinced that I’m the person who killed your father, your son, and your brother—but I am innocent ... I am so sorry for your loss. I really am. Sincerely.”

TROY DAVIS COULDN’T get a stay of execution—despite substantial new evidence supporting his innocence—in part because of the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. The Act was part of the Republican “Contract with America” signed into law in 1996 by President Clinton, who was pushed to bring a speedy and lethal conclusion to domestic terrorist Timothy McVeigh.

Read the Full Article