Yesterday a most interesting letter came across my desk. It was from a friend in California, sent to several of his friends, asking each of us to share our experiences in the effort to get books published. It invited balanced input, but the impetus for such a letter seemed clear: Those of us who fancy ourselves authors with some conscience and integrity find growing company when comparing the nightmares that have befallen us at the hands of publishers. Shuffling of editors, changes in price and publication date without notice, invisible promotion, and various unkept promises are increasingly common threads of the conversation.

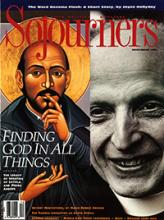

I find it both mildly comforting and deeply disturbing that I was not alone in experiencing all of these and more with my first publishing venture. The publishing house that was negotiating million-dollar-plus contracts with Johnny Cash and David Stockman at the time couldn't seem to spell the name of my community correctly or get my picture in focus on the book jacket.

But, of course, the two realities are connected. Even the names Cash and Stockman point to what is more and more blatantly the bottom line in the publishing industry. And if you are not "marketable" to the mainstream, for the most part you can expect to be treated with less than care and respect.

FORTUNATELY, THERE ARE some exceptions. When Sojourners editor Jim Wallis called Robert Ellsberg of Orbis Books in January 1989 with a proposal for a book that had to be completed by June of that year, Ellsberg moved heaven and earth to make it happen. On a virtually unheard-of timetable in the publishing world, Crucible of Fire: The Church Confronts Apartheid was out in time for Sojourners' national "Soweto Days" campaign.

Read the Full Article