There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. -- Sojourner Truth

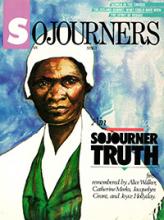

Sojourner Truth was a woman ahead of her time. This is evident in her life and work and is reflected in the speeches that have survived her.

Though in actuality powerless, she projected an image of power. Indeed, Sojourner Truth was a fearless creature. Even in the midst of the most cruel forms of oppression, in which she suffered physical and psychological abuse, Sojourner Truth refused to be silenced. Where she saw evil, she named it; where she experienced contradictions in the society, she identified them; where she saw deception, she exposed it.

Today slavery has been abolished, blacks vote, and women have been enfranchised. Yet oppressive structures continue to exist in our society. Oppression functions in some of the same ways, though it has taken new shapes in our contemporary context.

As in Sojourner Truth's time, black women are still perceived as less than white women, white men, and black men. Black women are still considered to be primarily servants, even as they relate to black men - hence, servants of servants. As they did then, black women's lives represent the point where racism, sexism, and classism converge.

Recognizing this, Sojourner Truth saw the inadequacy of the tendency of many to address only one form of oppression. While remaining a steadfast abolitionist and women's rights advocate, she consistently challenged black men for their sexism, white women for their racism, and white men for both their racism and sexism.

Read the Full Article