It’s December 2005, in a darkened New York theater. Onstage, it’s 100 years ago, in Germany.

“Why is it you want to be baptized?” a pastor asks the man who has just stepped into his church. The visitor struggles to answer. He’s Jewish, and he’s converting to Christianity because he is ambitious: Jews face professional obstacles, and he wishes to remove them.

But that’s not the reason that the pastor wants to hear. The man, refusing to profess a faith he cannot honestly claim, turns to leave. The pastor stops him. “Tell me,” he asks. “What is it you believe?” And the visitor turns, pauses, and replies: “I believe in science.”

He then launches into a hymn of praise to discovery and invention. “To be a scientist is to search the soul of God,” he tells the pastor. “For the briefest of seconds, to think what He thinks; to breathe what He breathes; to see through His eyes ... and then to act on it, to do good, to make it live, to—to give people something to believe in. We don’t want to be God, but we all try to be more like God, do we not? Is that not what we two believe? Is that not faith? Is that not holy?”

“Perhaps it is,” the pastor responds. And he proceeds with the baptism.

The visitor in this play was, in real life, a chemist named Fritz Haber, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1918. He is perhaps better known as the father of chemical warfare. The dialogue in Vern Thiessen’s play, called “Einstein’s Gift,” is fictional, but the central events are real: Fritz Haber was baptized in 1892. He devoted his life to science, innovation, and technical progress; the pursuit of knowledge was his true faith. And in many ways, it remains ours today.

OUR MODERN FAITH in science has gone through a few crises over the past century. It wasn’t always easy to believe in the glories of technology during the slaughter of European youth in World War I, or amid the horror of the Holocaust, or when people realized in the 1970s the full environmental cost of industrial growth.

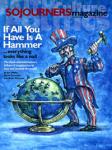

Yet this faith survives, and nowhere more vibrantly than in the United States. Whatever the problem, science promises a solution. Are you sick? A medical procedure should help. Can’t sleep? Take a pill. Does the nation face enemies? High-tech weaponry will surely vanquish them. Is global warming threatening the planet? Try hydrogen cars, or solar power. Schools don’t educate? Bring in the computers. Life has lost its meaning? Explore virtual realities and the endless frontiers of cyberspace.

There’s nothing wrong, of course, with using our brains to solve problems. Intelligence and curiosity are gifts from God, and renouncing them makes as much sense as refusing to walk or talk. When I get seriously ill, I’m sure I’ll search for the best-informed, most highly skilled medical care that I can find.

But our quest for technological salvation reaches far beyond mere appreciation for the results of human creativity. Most of my work in the past 20 years has involved watching and reporting on the scientific and engineering establishment. I’ve been struck by how much of this supposedly rational, calculating enterprise is fueled by trust, hope, and sheer blind enthusiasm. Much of it is based on “the substance of things hoped for; the evidence of things not seen,” to quote the definition of faith in Hebrews.

Often, it’s not the scientists themselves who subscribe most fully to this faith. They frequently know, better than anyone, the weaknesses of their craft and the limits to their knowledge. Instead, it’s political leaders who yearn for the cheap grace of a technical fix, and corporate executives who believe that all things are possible in the digital age.

Ronald Reagan certainly didn’t know many technical details about lasers and nuclear warheads when he announced his plan to make nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete” through the technologies of missile defense, a scheme popularly known as Star Wars. But Reagan had faith.

A friend of mine, an engineer, had a job 20 years ago in which he evaluated some details of Star Wars for a government contractor. Today, through a twist of fate, he’s involved in biomedical research in California. And he says nothing reminds him so much of Star Wars as the state’s current plan to pour $3 billion into laboratories working with human stem cells, in the hope that those cells will deliver cures for dozens of ailments. Both represent enormous bets—based less on hard facts than on hopes and dreams—that technology will deliver salvation.

There are many similar stories. Think of the enthusiasm surrounding computers in schools, or the Internet, or efforts to decode human (or plant) DNA. The powerful momentum behind such things often doesn’t depend heavily on solid data or even—as skeptics often assume—the political power of people who hope to profit financially. As I wrote several years ago about the push to create genetically modified crops, “Call it the romance of new things or the irresistible attraction of unexplored terrain, a place where—who knows?—dreams may come true.”

WHEN I FIRST stumbled across the story of Fritz Haber, I didn’t see it as a tale of faith. His life seemed, instead, to be a dramatic example of the moral ambiguity of science, of its capacity to both create and destroy.

In 1909, Haber found a way to “fix” nitrogen—a process that captures nitrogen atoms from the air and persuades them to combine with hydrogen to form ammonia. This converts nitrogen into a form that plants can digest—a momentous achievement, because nitrogen is for plants what protein is for humans; without it, they can’t grow. Today, hundreds of enormous ammonia factories around the world make fertilizer that ends up in crops and, eventually, in us. It’s become a pillar of life on earth—at least in places like China and India, which couldn’t grow enough food without it.

This accomplishment, for which Haber earned his Nobel, turned out to have a dark side. Long after he died, his invention encouraged farmers to turn fields into factories for food. Like most factories, they pollute. Most of the nitrogen that farmers pour on their fields doesn’t end up in our food but instead washes into creeks and rivers, where it causes ecological havoc.

But this is not what tarnished Fritz Haber’s reputation. No matter what the problem, Haber looked instinctively for a technological solution, and in 1915, with Germany at war, he persuaded his country’s military leadership to try out a new weapon—poison gas. Haber organized the necessary equipment, trained the troops, and eventually supervised the release of hundreds of tons of deadly chlorine gas at Ypres, Belgium—the first chemical attack in the history of warfare.

Two weeks later, Haber’s wife, Clara, killed herself. There’s no firm evidence as to why; Clara had long been despondent. But some of Haber’s colleagues believed that she was driven to despair in part by her husband’s military work.

Haber returned to civilian life unrepentant and remained for a time a prominent and honored member of German society. But in 1933, his world turned upside down. Hitler took power. Ordered to fire his Jewish employees, Haber resigned in protest. He spent the last six months of his life in exile, wandering Europe, looking in vain for a new homeland. He died of heart failure in a Swiss hotel room in 1934 and was buried in a cemetery alongside the German border.

A final, almost unspeakable irony of Haber’s life was yet to come. The great cause of his life, his science, would be turned against his own people. During the 1920s, Haber’s laboratory had developed Zyklon-B, a poisonous gas to control insect pests. Ten years later, this chemical was used in Nazi death camps in which some of Haber’s own relatives died.

Haber couldn’t have foreseen all this, but he did have a premonition. “The great technical accomplishments that the past 50 years have granted us,” he wrote to a friend a few months before the Nazi takeover, “are like fire in the hands of small children.” It was as close as he ever came to renouncing the cause to which he’d devoted his life.

I WROTE A BIOGRAPHY of Haber and arrived at the end of the story convinced that it was, at its core, a tale of short-sighted or misguided faith in technological progress. I dedicated the book to my parents, and I played with the idea of paying tribute in a few words to their faith, which is deeply rooted and true. In the end, though, I wasn’t satisfied with any of the words that came to me, and I dropped the idea.

So when I opened my copy of the play “Einstein’s Gift,” I was immediately struck by the words of Thiessen’s dedication: “to my parents / for keeping the faith.” I was struck even more by the play when I saw it come alive onstage. It seemed to be, even more explicitly than my book, a story about faith.

I called Thiessen, who assured me that I hadn’t imagined this. “The play for me has always been about belief, or faith,” he said. “Everyone in the play wants something to believe in; something to hold onto. And that connects to me personally.”

As it turns out, Thiessen and I share more than a fascination with Fritz Haber. We both grew up in large Mennonite communities: he in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and I in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Ralph Waldo Emerson said that all biography is autobiography. I can’t speak for Thiessen, but I’m pretty sure that my own history influenced my response to Fritz Haber.

In the community where I grew up, religious faith pervaded every aspect of life, from the clothes we wore to the songs we sang and the schools that we attended. This interweaving of the spiritual and material seemed natural, even inevitable. I never quite let go of the idea that our lives express spiritual convictions, whether we’re conscious of this or not. And the contemporary thirst for scientific solutions looks to me like a quest for our own thoroughly modern messiah.

Daniel Charles is author of Master Mind: The Rise and Fall of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Laureate Who Launched the Age of Chemical Warfare and a member of Community House Church in Washington, D.C.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!