It is an image that has never left me since hearing of the incident. Marienella Garcia had risked imprisonment and death for years by publicly exposing the human rights violations of the Salvadoran government. In March 1983 she was found dead after being abducted and tortured.

The government forbade a public memorial service in the church where her body lay. Soldiers were dispatched to guard the church entrance and ensure that only the priest would be present at the Mass.

Fearing the consequences if they were to disobey this governmental decree, most people stayed away. But some of the poorest peasants with whom Marienella Garcia had worked went to the church that day and walked right past the guards into the sanctuary. One by one they kissed their beloved friend and advocate and said their goodbyes while the guards looked on and did nothing. Later that night, under the cover of darkness, the army raided the homes of these mourners, arresting the men and raping the women.

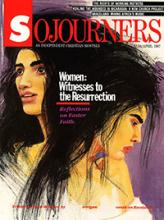

Until I heard that story, it had never really dawned on me how the women who went to the grave of their beloved friend that Easter morning had done so at great risk to themselves. For it was the grave of a convicted political criminal. Guards stood watch, ready to report the identities of those who dared expose themselves as his supporters. Why this never dawned on me before is strange, considering that we are told how the rest of the disciples were in hiding, laying low, avoiding guilt and punishment by association.

And it strikes me that the courage of those women is the first sign of a resurrection faith on that morning, even before an empty tomb is discovered or Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene and calls her by name. Love has already proven stronger than death as these women arise and go to the grave. The strength of their love, expressed in grief, has overcome the fear that apparently still has the others in its paralyzing, deathly grip.

Read the Full Article