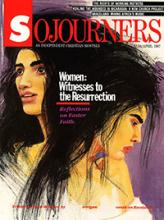

For the last several years at Easter, the image of women as witnesses to the Resurrection has been an important aspect of our personal study and community worship. According to the gospel accounts, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Joanna faithfully returned to the tomb, prepared to attend to Jesus' body, and discovered it was empty. They were the first ones to know that Jesus' promise to rise again had been kept.

Women all over the world are today faithfully ministering to the bodies and souls of the oppressed and needy. And their willingness to face pain and sometimes danger because of that work creates opportunities for them to witness Jesus' resurrection power.

We have asked several women to share their understanding of resurrection faith and power at this Easter time. We hope their words will challenge and encourage women and men of faith to see the resurrected Christ among us.

-The Editors

In 1980 I was serving a 30-day sentence in the D.C. jail for holding a banner in the driveway at the White House. My second week in jail included Easter, and I attended the Catholic services. I flushed with shame and anger as the priest spoke of jail being our tomb, and release from prison an experience of resurrection.

True! The jail is tomb-like. But there was life there of which - to judge from his remarks - the priest knew nothing. There was hope that women built together in that tomb; there was love that they shared in a thousand small and large ways to make "the wilderness and dry land glad, the deserts rejoice and blossom " (Isaiah 35:1).

Read the Full Article