In this age of third-wave feminism, many Americans may not realize that Christian women continue to struggle with what many would deem outdated gendered notions. This includes things such as a woman’s calling being second to her husband’s, women as unwitting temptresses who therefore must hide their bodies, and that women may not lead (or sometimes even speak) in church. Both external and internal pressures and fears have historically kept women silent on these matters.

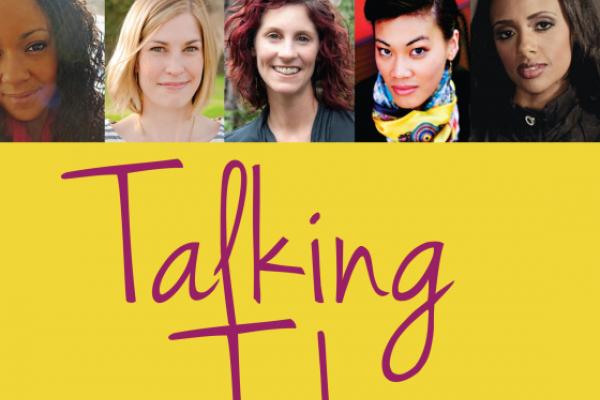

In the recently released Talking Taboo: American Christian Women Get Frank About Faith, 40 women under 40 address head-on many of the taboos remaining at the intersection of faith and gender, and how they are stepping out of historical oppression to make real change within the church.

In her book Lean In, author Sheryl Sandberg notes that while women are outpacing men in colleges and graduate schools, one cannot see this translate to positions of power within corporations. For this imbalance to be righted, Sandberg asserts that women must take charge of their circumstances: “The shift to a more equal world will happen person by person. We move closer to the larger goal of true equality with each woman who leans in.”

This is no less true of women in the church, and leaning in is exactly what the essayists of Talking Taboo are doing.

While Sandberg focuses on issues such as long work hours, daycare, and more flexibility for working moms, the common, though not exclusive, themes of Talking Taboo are sexuality and biblical interpretation.

Read the Full Article