A quarter of U.S. adults do not affiliate with any religion, a new study shows — an all-time high in a nation where large swaths of Americans are losing faith.

But while these so-called “nones” outnumber any religious denomination, they are not voting as a bloc, and may have little collective influence on the upcoming presidential election.

The rapid growth of the religiously unaffiliated, charted in a survey released by the Public Religion Research Institute on Sept. 22, is raising eyebrows even among those who follow trends in American religiosity.

The number of unaffiliated young people has jumped fourfold since 1986 — from 10 to 39 percent. And overall 1 in 4 Americans call themselves unaffiliated, up from 1 in 5 in 2012.

“Wow, it does seem like a big jump,” and it speaks to the nearly universal struggle to keep people in the pews, said Randall Balmer, an Episcopal priest who chairs Dartmouth College’s religion department.

“It is for many almost axiomatic how difficult it is to pass religious passions from one generation to the next.”

Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton may be pleased to learn that these numerous nones overwhelmingly favor her over her GOP rival Donald Trump — 62-21 percent in the poll, which was conducted in late July and early August.

But despite their heft, the religiously unaffiliated is no voting bloc.

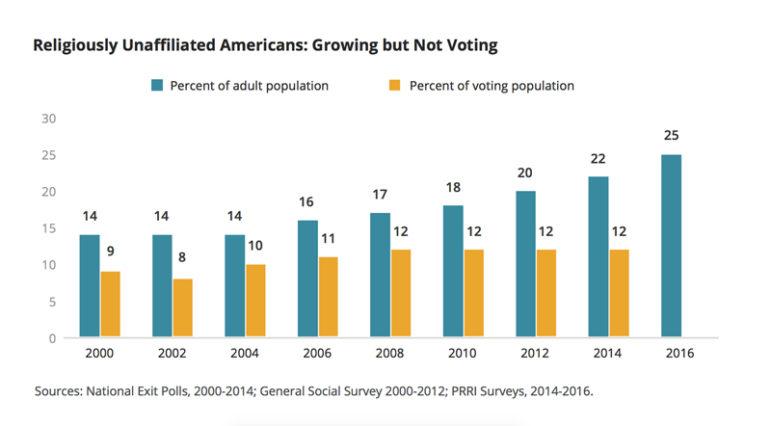

A second major takeaway from the study: though growing, the group is not voting.

In 2004 the nones comprised 14 percent of the public but only 10 percent of voters. In the last presidential election they jumped to 20 percent of the public, but inched up only to 12 percent of voters.

thumbrns-prri-survey092116c-771x426.jpg

“For me the big question is ‘will this group come out in November and really throw their weight around?’” said Daniel Cox, PRRI’s research director and a co-author of the study. “They could have considerable impact on the political direction of the country but have so far chosen not to do so.”

PRRI’s survey of 2,201 American adults is far from the first to try to capture the size of the nones, the reasons for their lack of religious affiliation and their role in politics. But the report on the survey, titled “Exodus: Why Americans are Leaving Religion — and Why They’re Unlikely to Come Back,” takes one of the most detailed snapshots of the group to date.

The survey also hints at how their growth may portend a nation where religion no longer informs a predominant cross section of Americans on what it means to be a good person and citizen.

“I wouldn’t say we are destined to become a completely secular country by any means, but we are venturing into uncharted waters in terms of our religious identity,” said Cox.

“Historically most people consider this country a Christian nation, or a country where Christianity has been central. We may be entering a period where that is no longer true.”

(The study follows the publication earlier this year of a book by study co-author and PRRI founder Robert P. Jones, The End of White Christian America.)

According to the poll — which has a margin of error of plus or minus 2.5 percentage points — the nones have outstripped the single largest religious group of Americans: Catholics, who are now 21 percent of the adult population. The next largest group, white evangelical Protestants, represent 16 percent.

Also notable in the PRRI study are its finding on youth, and the strength of their disinclination toward religion.

“And there’s not a lot of evidence that they are rushing back to the pews when they get older,” said Cox.

While the vast majority of religiously unaffiliated Americans grew up with a religious identity and then dropped it, an increasing percentage of nones started out that way — with no religion to leave.

According to the study: About three-quarters (74 percent) of those under 50 who were raised in unaffiliated homes remain unaffiliated as adults. That compares to half (49 percent) of those 50 and older who were raised without a religious identity and who still do not identify with a religion.

Roxanne Stone, a former editor at Christianity Today who now studies millennials and their faith at the nonprofit Barna Group, said she for one was not astounded to learn that the number of unaffiliated — particularly among the young — has grown exponentially in just a few years.

She sees it in her own number crunching on young peoples’ spiritual lives, but also in her life as a millennial Christian. Her stated intention to attend church on Sunday, she said, has been met by members of her age cohort asking: “People still do that?”

Young people are generally not joiners, she said. “There’s a growing sense of disillusionment with institutions and this plays into why they don’t want to vote.” Many, she said, admire neither of the major party’s presidential nominees, and have little faith that government or other institutions can make any difference.

Stone traces this apathy to the dwindling importance for many young people of community groups and other institutions — including churches — in this increasingly mobile society. Less religious affiliation doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less likely to be believers than they used to be, she added.

“They weren’t going to church necessarily out of belief — but for community. But there are millions of apps for finding friends now.”

Some secular Americans have also noted that while politicians frequently use religious language to cater to evangelicals and other religious Americans, they have been slow to recognize the largest fraction of the “religious” electorate — the irreligious. At the Reason Rally in Washington, D.C., in June, nonbelievers hoped to show that they too, can wield political power.

The PRRI poll does find some diehard nonbelievers — people who want nothing to do with religious institutions. But it also found others among the unaffiliated who harbor some positive feelings toward religion.

The nones are hardly uniform in their disbelief and disengagement.

To better understand the group, PRRI researchers sorted the nones according to their answers to two questions: one about the personal relevance of religion, and the other about their perceptions of the social benefits of religion. With these responses Cox and his team found the nones fell into three distinct subgroups:

- Rejectionists — The largest subgroup by far (58 percent) says religion is not important in their lives and does society more harm than good.

- Apatheists — At 22 percent, they say religion is not personally relevant to them but generally beneficial to society.

- Unattached believers — This 18 percent of the unaffiliated say religion is important to them personally.

Unattached Believers — whose members among the unaffiliated are most likely to say they regularly contemplate God and religion — skew older than the Apatheists and Rejectionists.

But Balmer — the Dartmouth religion scholar — is not giving up on the young, and said they have not closed their ears to religious teaching.

“I would love to see the response to a candidate who spoke honestly and candidly about values, religiously informed values, and who took seriously the words of Jesus to care for ‘the least of these,'” Balmer said.

“You got a glimpse of it in who I saw as the most religious candidate in the 2016 election,” Balmer continued. “Bernie Sanders. Listen to him. He sounds like a Hebrew prophet, and the millennials responded.”

Sanders, a U.S. senator from Vermont, identifies as Jewish but not religious. He spoke earnestly on the campaign trail about the poor and working class — who he said America has neglected — and garnered more votes from young people than Clinton and Trump combined.

The PRRI survey, conducted in partnership with Religion News Service, was funded by the Henry Luce Foundation and the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!