Climate change affects the poorest the hardest. Most things do. In the parts of the world where climate change is most prevalent, it is those who have done the least to cause it that are bearing the brunt of its effects.

It is the Malawian farmer whose crops have failed because the seasonal rains didn’t start at the usual time. It’s a Bangladeshi who can see the sea-levels rising around her town year after year, and has nowhere to go. It’s even an American family whose food bill grows ever larger because of the stresses that a changing climate is having on food security worldwide.

These are neither the people nor the organizations that have spent decades turning a blind eye to their responsibility as good stewards of our environment. They are not the people who, in the face of more and more extreme weather patterns, turn an issue of human survival into an ideological war.

It is for them that we must adapt.

Now, it may be unfair to place the blame for the predicament we find ourselves in on the businesses and individual people who have brought us through the Industrial Revolution, the technological revolution and beyond. The publicity around and knowledge of what climate change is and what effects it has on the world and its population are relatively recent. But that does not give us an excuse to waste any more time.

We adapt all the time. Forty years ago, if I had wanted to communicate this message to you, I would have had to write you a letter. A century ago, if I had wanted to leave the United Kingdom and move to the United States for a year (as I recently have), it would have taken six weeks on a boat to get here. When I returned from visiting England for the hoidays a week ago, it took me eight hours.

When the opportunity arises, we adapt.

Why should our thinking be any different when it comes to our environment? Our planet is changing and we should be attentive to this – and duly proactive in our response.

The effects of a changing climate are wide reaching and by no means limited to environmental challenges. Climate change is a security issue. It is a human issue. And it is also a moral issue.

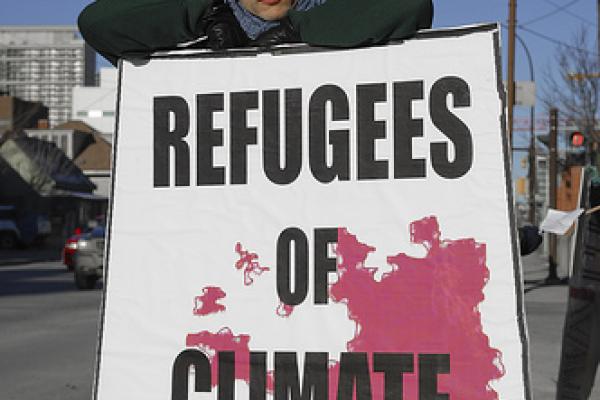

Climate change as a security issue. Let’s linger on this for a moment. What does the climate have to do with defending our borders or with international relations? First, there is the issue of “climate refugees." This (or other expressions thereof, such as "environmental migrant’) is a term that is used with increasing regularity in the world of international politics.

People are being forced to leave their homes, communities and countries because of the impact that the changing climate is having on their safety and security. And where do they go? Yes, some relocate to different parts of the country, but others are forced to cross borders. If action isn’t taken, this is going to become more and more common, and will place more and more pressure on already struggling communities.

As sea-levels rise along the coast of Bangladesh, where will the huge population move to? Yes, inland initially. But beyond that? India? Burma? I’m no expert in South Asian politics, but I have a feeling that mass migration from Bangladesh to India would cause some tensions on both sides of the border. And I’m sure this example can be used in other parts of the world where similar effects are being felt.

Climate change is a security issue when it comes to food and water security as well. Rising sea levels and changing/more extreme weather patterns are making water supplies increasingly vulnerable. Some have gone so far as to call water “the new oil”. If water becomes a commodity in the same way that oil has — and therefore susceptible to exploitation — then it is both a security and moral issue. Whatever we can do to avoid this must be done.

The same goes for food security. As changing wreathing patterns affect water supplies, they also affect farming and crop production. Not only is this a crisis that is and will spell disaster for subsistence farmers around the world, it also is an issue in our own food markets. Uncertainty around food production will result in food prices rising are unsustainable levels, which is not something that is desirable at the best of times, let alone during a global recession.

So how do we – as individual people, the church, the developed world and the world at large – adapt? What does that look like?

Well, at the top level, it means working together and recognizing that this is an issue that will neither go away nor fix itself. It is about finding new and innovative ways to produce and consume energy, and use and preserve our natural resources. It is about not being afraid to move away from received wisdoms.

As the developed world, it’s about recognizing our over-dependency on unsustainable energy sources, and our flagrant waste of finite resources such as food and water.

Recognizing and then adapting.

As a church it’s about speaking into what it means to be stewards of our environment, as well as refusing to turn our backs on the poor, vulnerable and voiceless of this world.

And as individual persons, it’s about making a conscious decision to go against the grain, to say that ultimately my actions do have an impact and if I am not willing to change, then why should anyone else?

This is our starting point. We adapt, and in doing so, we help others to adapt. And if we do, we might just save some lives. And our planet.

If you want to learn more about climate change adaptation, below are some useful resources.

- UNFCCC Climate Change: Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Adaptation in Developing Countries

- The Economics of Climate Change Adaptation (World Bank)

- Environmental Protection Agency – Climate Change

- Adaptation United (Tearfund)

- Climate Change Adaptation (Oxfam)

Jack Palmer is a communications assistant at Sojourners. Follow Jack on Twitter @JackPalmer88.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!