Jan 29, 2016

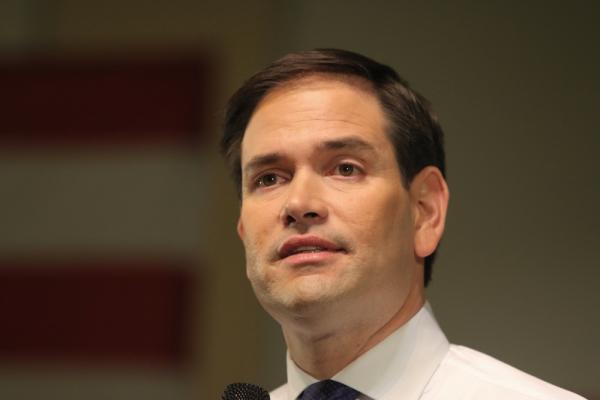

Rubio is doing his best to sound like an evangelical Christian. Last night he spoke about his faith more than he has done in all the other GOP debates combined. From what I have read, Rubio attends both a Catholic church and an evangelical megachurch. His spiritual commitment seems sincere. I have no doubt that he is a man of faith. But the way he used his religion last night made the Christian gospel subservient to his political ambitions.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login