Last spring, I heard a terrific talk from Shane Claiborne at the Festival of Faith & Writing. Claiborne, a prominent voice in progressive Christian circles, lives in Philadelphia’s inner city, where he and the other inhabitants of the Simple Way community practice a “new monasticism.”

They value hospitality and communal living, seek to build relationships with those living in their neighborhood, and are concerned with issues around poverty and wealth, power and violence. From the descriptions I’ve read, the Simple Way practices similar values to the Church of the Saviour in Washington, D.C., where I worshiped for most of my 20s. The Church of the Saviour had the unusual distinction of taking both Jesus and social justice seriously. It was a community in which I was comfortable speaking like an evangelical, while voting and approaching social issues like an Episcopalian.

Listening to Claiborne speak back in April about justice and love and how our stories illuminate God’s kingdom, I felt at home. Here was the kind of guy I used to worship with in my earnest urban-dwelling days. His message, his words, and his stories felt intimate, familiar, and inspiring.

That is, except for this one story:

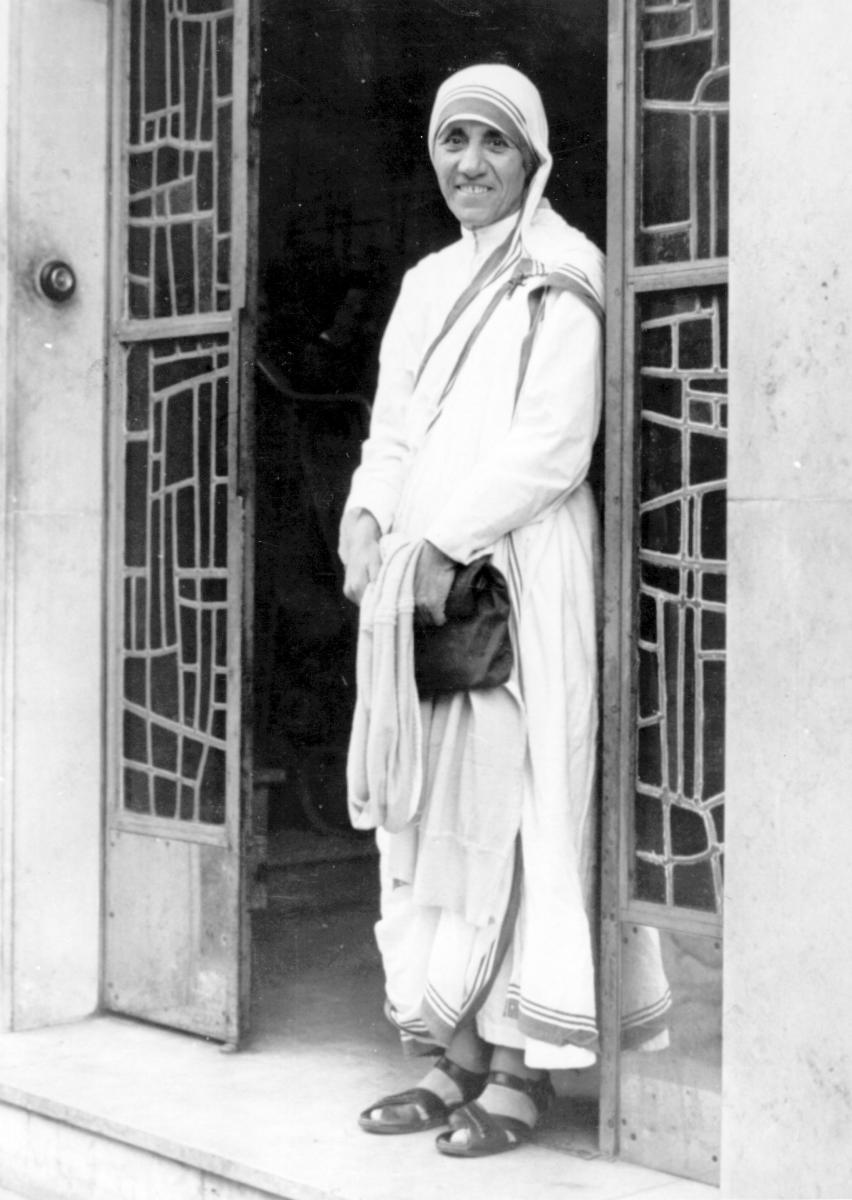

During Claiborne’s time with Mother Teresa in Calcutta, he noticed, when Mother Teresa took her shoes off for daily prayer, that her feet were knobby and deformed. He eventually asked someone what was wrong with Mother Teresa’s feet. The person explained that Mother Teresa and her sisters relied on donations for everything, including their shoes. When a load of donated shoes would come in, Mother Teresa consistently chose the worst pair of shoes for herself. As a consequence of wearing substandard shoes, her feet had deteriorated.

Eyes shining, Shane Claiborne asked all of us in the audience that April night, “What would the world be like if we all chose the worst pair of shoes for ourselves?”

It was a rhetorical question, the answer clear: The result would be unequivocally good. Claiborne was talking about shoes, but obviously, he was talking about more than shoes. He was talking about the radical power of sacrificial love.

While I can’t argue with the radical power of sacrificial love, I would answer Claiborne’s question very differently.

Question: What would the world be like if we all chose the worst pair of shoes for ourselves?

Answer: We would all have messed-up feet, and would struggle to be of service to anyone because our feet would hurt so damn much.

Claiborne was, of course, speaking symbolically. Nevertheless, the story was about Mother Teresa’s very real, very non-symbolic feet. I can’t speak for Mother Teresa. I don’t know if her feet hurt. If they did, I don’t know if she ever struggled mightily to keep on walking and serving and tending in spite of that pain, or if she had the mental fortitude to block it out.

I do know, however, that my feet frequently hurt. As do my knees, my hips, and my back. And this pain, far from being a symbolic self-sacrifice is just…well…a pain. And it very much affects what I can and can’t do, for my family and for God’s people.

Claiborne’s job that night was to tell stories that might draw us closer to understanding our place in the ultimate story, in which God is calling us to work that will bring God’s kingdom closer to reality. But what I heard in the Mother Teresa story didn’t come across as good news. What I heard were assumptions, the same tired old assumptions, about what kinds of bodies are required to do the real work of the kingdom.

Assumption 1: Our bodies’ needs (for a decent pair of shoes, for example) are not important as we consider how to minister with others and respond to God’s call.

Assumption 2: Bodily pain and disability doesn’t (shouldn’t?) influence what we are willing to do for God and God’s people.

Generally speaking, of course, the people who make such assumptions are those whose bodies are robust, healthy, and largely pain-free. And given that many popular, charismatic, high-profile people who are leading our national conversations about how to build up God’s kingdom are young, energetic folk like Shane Claiborne, it becomes easy to assume that robust, healthy, pain-free bodies are the norm. But they’re not. There are lots of people like me, who have some clear physical or psychological disability that significantly influences what our bodies and spirits can and cannot do. And then there is our rapidly aging population of people who were once robust, healthy, and pain-free, but who are becoming arthritic, hobbled, and hunched.

Do our models of Christian service adequately encompass people whose bodies don’t work all that well, who live with chronic pain, who can’t even think about accepting the worst pair of shoes because without decent shoes they can’t walk? No, they don’t. Even in the progressive Christian circles in which I feel most at home—circles in which we strive to name and chip away at class and race and gender barriers—we often fail to even acknowledge how life with a failing, broken, pain-filled, or disabled body can drastically alter what we can and can’t do in the name of God and out of sacrificial love. Despite being very aware of the privileges that come along with class, race, or gender, we still largely fail to recognize how often the privilege of a healthy, functional body is simply assumed.

Furthermore, we tend to look up to those willing to forgo various bodily comforts and securities as models of what it means to follow Jesus Christ in 21st-century America. We look up to people like Chris Travis, who wrote a book about spending two years teaching in a dangerous, failing urban middle school. We look up to people like Shane Claiborne and his companions, living communally in inner-city Philadelphia. We look up to people like Ann Voskamp, who lives among “gravel roads and cornfields,” homeschooling her six children and writing while her husband farms. In the Church of the Saviour community where I first tested out my adult faith, I worshiped alongside people who chose to live in D.C.’s roughest neighborhoods even though they could afford to live elsewhere, who regularly traveled to impoverished nations for various service projects, who biked everywhere wearing their “One Less Car” t-shirts.

It is folly for me, dwelling in my broken and fragile body, to aspire to such ways of living.

I cannot teach in an unruly middle school as Chris Travis did. He received a bruise to the face in a skirmish that would have likely left me with several broken bones.

I cannot live in an impoverished urban neighborhood where biking, walking, and busing are the primary modes of transportation. I can’t bike. I can walk only limited distances. I can’t negotiate a city bus easily, particularly if I’m carrying anything. My minivan—that ultimate symbol of the gas-guzzling, convenience-loving, wasteful American way of life—is an instrument of freedom for me.

My body’s limitations require me to live by a fairly strict calculus of energy conservation. I have learned through trial and error that if I want to have energy to do what is important as well as what is necessary, I cannot: hang clothes out to dry (I use the dryer), walk to do my errands (I drive), grow my own vegetables (I buy them), frequent several different stores to get the most sustainably grown and/or least expensive food (I can barely handle one or two grocery runs per week), cook meals entirely from scratch (I rely on a combination of from-scratch and convenience foods), attend lengthy gatherings at which I will be forced to either sit or stand for very long periods (either one leaves me hurting), and…I could go on, but I think you get the idea.

I’m not looking for sympathy. I live a comfortable, happy, and quite privileged life with my family. No, I can’t go live in a developing nation where good medical care is not assured, work on an organic farm, or teach an unruly group of teenagers. But I can write. I can raise my children. I can lay my hands on hurting people in my church’s weekly offering of healing prayer. (Although I’ll also point out that no one ever holds up the life of a minivan-driving, suburban-dwelling, stay-at-home mother as an example of sacrificial love and authentic ministry—an observation for another post.)

These efforts are enough and more than enough. I know that. They are more than enough, because they are the works to which God has called me. Me. And there are many vital works that bring God’s kingdom closer without need of muscle and bone—all kinds of art, prayer, tangible comforts offered to those who are sick or grieving.

Shane Claiborne sees the wearing of flimsy shoes as an inspiring example of sacrificial service. I see it as either terrible stewardship of one’s perfectly good feet (for my skeletally healthy brothers and sisters), or an impossibility (for me). (In fact, my disability requires me to buy expensive shoes with good support, and then plunk down an additional $100 per pair to have the shoes altered for my crooked body and screwy feet).

But the wonderful thing, about God’s kingdom is that there’s room for both me and Shane Claiborne within it. “There are different kinds of gifts, but the same Spirit distributes them.There are different kinds of service, but the same Lord. There are different kinds of working, but in all of them and in everyone it is the same God at work…Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. For we were all baptized byone Spirit so as to form one body—whether Jews or Gentiles, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink. Even so the body is not made up of one part but of many.” — from 1 Corinthians 12.

Confronted daily with the reality of a body whose parts are most definitely not all healthy or strong, I am perhaps better acquainted than more able-bodied believers with just what a perfect metaphor the human body is for the variety of gifts with which God equips us for ministry.

Nevertheless, in progressive Christian circles, certain kinds of work still tend to get the good press—active, uncomfortable, slightly dangerous work. This is precisely the type of work that people with many kinds of disabilities, as well as aging Christians learning to live with bodies that don’t operate as they used to, cannot do. The vibrant presence of those with far-from-healthy bodies in our faith communities requires that we get serious about honoring the full diversity of gifts and ministries, and not just the most active gifts and ministries that make for the most gripping stories.

It’s unlikely that a speaker will regale thousands of listeners with stories of prayer-shawl knitting at the next Festival of Faith and Writing. But we can still be intentional about honoring the many ways that all of God’s people can help advance God’s kingdom—even those whose screwed-up feet are, by necessity, covered with a really great (and pricey) pair of shoes.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!