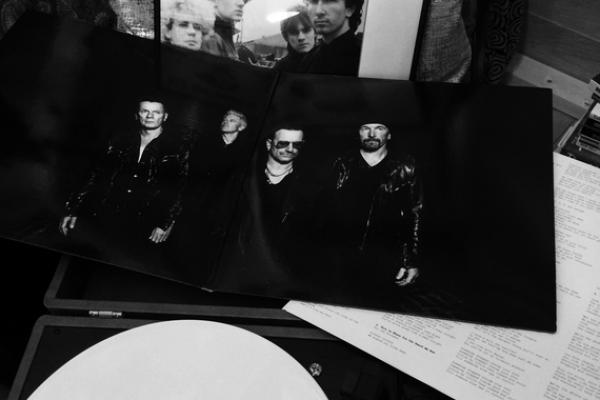

Sunday evening I did something I haven't done in close to 30 years: I went to an actual record store and bought a brand-new U2 album on vinyl, took it home, pulled out the turntable, put on my headphones, sat on the floor, and stayed up way too late reading the liner notes and listening to the songs over and over again.

Lord, how I've missed this particular ritual.

When I was a teenager, late Sunday nights were when I indulged my secret pleasure by listening in bed (clandestinely so as not to incur the wrath of my parents for being awake well past my bedtime) to the "King Biscuit Flower Hour" on WPLR, the classic rock station in New Haven that was one of two (the other being a horrendous pop-40 station) that came in clearly on the FM stereo in my upstairs bedroom.

I listened, religiously, every Sunday night for years, hoping to hear a song by one of the British New Wave bands of which I was fond, or, if I was particularly lucky, by my favorite band on the planet: U2.

Sometimes weeks would go by without hearing a U2 song on those late Sunday nights, my ear pressed to the transistor radio secreted next to the pillow on my twin bed. But then, like a bolt of lightning — I'd hear Bono's voice or Edge's guitar begin to keen. It was a wee bit magical, although in retrospect today I might call it sacred.

All the waiting and listening was worth it. Always.

Read the Full Article