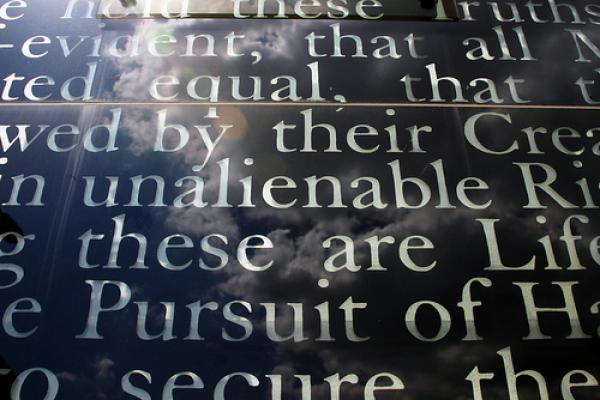

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness (The Declaration of Independence, 1776)."

These words are some of the most familiar and beloved in the English language, as they offer a moral vision for humanity, and a standard to which the United States of America should strive.

While such expressions of freedom should indeed be cherished, we often forget the harsh reality that many contributors of the Declaration of Independence were also active participants in the brutal act of slavery. As the English abolitionist Thomas Day wrote in 1776: “If there be an object truly ridiculous in nature, it is an American patriot, signing resolutions of independency with the one hand, and with the other brandishing a whip over his affrighted slaves.”

In addition to racial inequality, while Abigail Adams reminded her husband John to “remember the ladies” during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, her warnings were mostly disregarded, and as a result, women were also marginalized, and they were relegated as dependents of men, without the power to own property, make contracts, or vote. In other words, John Adams’ reply to Abigail’s challenge was far from considerate: “As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh …”

Read the Full Article