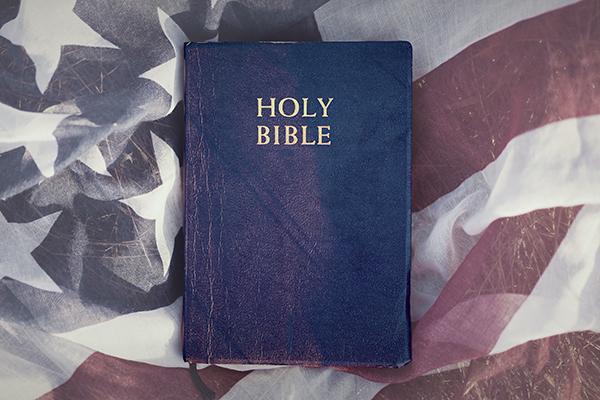

The Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection on the United States Capitol building thrust the influence of Christian nationalism onto the world stage. Videos and photographs of the spectacle reveal an event more akin to a religious revival than a political rally. While the Trump administration billed the event as a “Save America Rally,” attendees showed up with Bibles, “Jesus for President” signs, flags emblazoned with “Make America Godly Again,” life-size crosses, placards of a White Jesus adorned with a MAGA hat ... and guns and bullet-proof vests. One Catholic priest even performed an exorcism inside the Capitol to thwart a satanic figure who is allegedly influencing progressive members of Congress.

No mere political rally

As I’ve studied these images and videos, what has jarred me the most is the sheer number of insurrectionists who are seen passionately praying to and worshiping Jesus as they violently lay siege to the heart of American democracy (a siege inspired by conspiracies of a stolen election). This was no mere political rally; it was a mountain-top spiritual experience for many insurrectionists, rooted in the conviction that America is being overrun by immigrants and progressive ideals and is on a path to spiritual ruin. As Guy Reffitt, the first insurrectionist to be sentenced, said about Jan. 6, 2021 : “I was willing to die. I had a very epic point in my life, actually.”

The insurrection—or, better yet, “revival”—led to the death of five people and the largest prosecutorial undertaking in American history. It offers an urgent reminder that another pandemic rages on in the United States that is unregulated by vaccines, masking and social distancing. This other pandemic is a moral and theological one built on a perversion of the life and teachings of Jesus. This other pandemic has torn families and friendships apart and has caused big “T” and little “t” trauma in our communities. While sneaky, our moral pandemic has gone viral and demands to be named, defined and resisted as it chips away at the foundations of democracy and erodes the church’s public witness. Our moral pandemic is White Christian nationalism.

White Christian nationalism and American exceptionalism

The influence of White Christian nationalism is nothing new in the 2020s. Its marriage to state power, American exceptionalism, gun culture and White supremacy has deep roots in 20th-century Evangelicalism, along with a “deep story” that goes back to what Philip Gorski and Samuel Perry, in their book The Flag and the Cross: White Christian Nationalism and the Threat to American Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2022), call “White Protestant chosenness” in the late 17th century. As Kristin Kobes Du Mez provocatively writes in her book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (Liveright, 2021), “In reality, evangelicals did not cast their vote [for Trump] despite their beliefs, but because of them.”

Recent work by sociologists and historians has unpacked how we got here and how to define what Christian nationalism is. However, questions of how to interrupt its influence nonviolently remain murky at best and wholly unsophisticated at worst. What should Christians against White Christian nationalism do? And how do we nurture faith communities to increase their immunity from nativist gospels, militarized White-Jesus idols and xenophobic personality cults that incubate theologies of oppression? While disorienting Christian nationalism demands a large-scale, interdisciplinary and ecumenical movement, there are a few things that we can do in everyday life right now.

Step 1: Break the silence

The first thing Christians against Christian nationalism can do is to break silence and create spaces to define and talk about White Christian nationalism. It is impossible to resist something unless you can name the objects of your resistance. For most of us, this probably means looking inward before looking outward: toward our own congregations and families. We are living in the midst of a theological crisis as much as a political one—a spiritual contagion spread by biblical illiteracy, superficial meme theology and gross distortions of the life of Jesus.

We need to publicly name this theological contagion in our communities for what it is, along with the ways that it flourishes online through misinformation, algorithmic echo chambers and psychological manipulation that can lead to radicalization. One recent study even showed that sharing fake news has little to do with being misinformed or one’s education level and much to do with hating one’s ideological opponent. Silence and deference are not effective strategies to protest the virality of hate, misinformation and toxic theology. As Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., memorably said , “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” This is the church’s moment to show up. Breaking silence is step one; defining Christian nationalism is step two.

Step 2: Define Christian nationalism

But how should we define Christian nationalism? Christian nationalism, in short, is a worldview where one’s theological imagination is co-opted by state power. The problem with Christian nationalism is not that it is racial and ethnic. The problem, rather, is that it is supremacist and ethnocentric. It exchanges the church’s loyalty to the Lord of Peace and citizenship in God’s multiracial and unarmed kingdom for a false god fashioned by the myth of American exceptionalism.

Christian nationalism, therefore, is a form of political idolatry in that it distorts our knowledge of God and neighbor through a xenophobic, nativist and violent gospel of “us” (White English-speaking Christians) versus “them” (BIPOC, LGBTQ+ persons and immigrants). In this sense, Christian nationalism is a worldview in which one’s ethno-racial identity becomes a more powerful controlling narrative than one’s baptismal identity “in Christ.” Such loyalty to state power can even lead Christian nationalists to endorse state violence, police brutality and personal armament as expressions of faithful discipleship. In so doing, it turns a blind eye to the unanimous witness of the New Testament that the way of Jesus is a way of peace.

The ways in which Christian nationalism perverts the life and teachings of Jesus under the guise of patriotic piety are not hard to illustrate. Based on data from the Baylor Religion Survey, sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry have shown that many Christian nationalists have a high view of biblical authority but, ironically, are disconnected from faith communities and are often at odds with biblical ethical values like hospitality, peace and justice for the poor and marginalized.

How do we create pathways for return, recovery, dialogue, repentance and reparation—in community? What do sobriety and repentance look like for those caught up in the whirlwind and addictions of hate and fearmongering? And, most importantly, how do we foreground protecting the vulnerable in our midst who are most at risk of experiencing harm from White Christian nationalists?

Step 3: Preach the whole life of Jesus

Here, we need collective discernment and spaces to share wisdom. That said, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel: the life and teachings of Jesus offer us a model for resistance, disruption and renewal. After all, Christians against Christian nationalism living in the post-Trump world are hardly the first generation of believers to negotiate and resist political idolatry. Both ancient Jewish and early Christian communities lived in a world chock-full of political idolatry, including divine warrior kings, nationalist fantasies, imperial violence and racism.

In following the whole life of Jesus—from womb to empty tomb—Christ followers became active participants in God’s work of renewal and reconciliation by “proclaiming peace through Jesus Christ” (Acts 10:36). Can we do the same by building a church-led social movement of anti-oppression, Jesus-following Christians who—collectively!—bear witness to the myriad ways in which White Christian nationalism is incompatible with the way of Jesus?

This is step three in disrupting our moral pandemic: to preach the whole life of Jesus. In preaching the whole life of Jesus, we are invited to not reduce the gospel to a myopic message of personal salvation separate from God’s cosmic purposes of reconciling humans to God and humans to one another. In preaching the whole life of Jesus, we are invited to incarnate and become active participants in the ways of Jesus in our world today, including the ways that neighborly love, inclusive table fellowship, divestment of money and care for the poor interrupt patterns of oppression and sin in our world.

Certainly there are other strategies of resistance that urgently warrant our attention and discussion, but a place to start is to (1) break our silence, (2) define and discuss White Christian nationalism and (3) proclaim the good news that, in Jesus, the God of Israel is at work to build a just world where we can live in peace with God and with one another even as we celebrate, maintain and live into our own cultural and ethno-racial differences.

Want to learn more?

Want to learn more about how pastors, congregants and organizers can challenge Christian nationalism? Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS) is working to resource the Church to live the whole-life calling to be Jesus-followers. Through AMBS, I am leading a webinar on political idolatry and a four-week online short course titled, “ Resisting Christian Nationalism with The Gospel of Peace .”