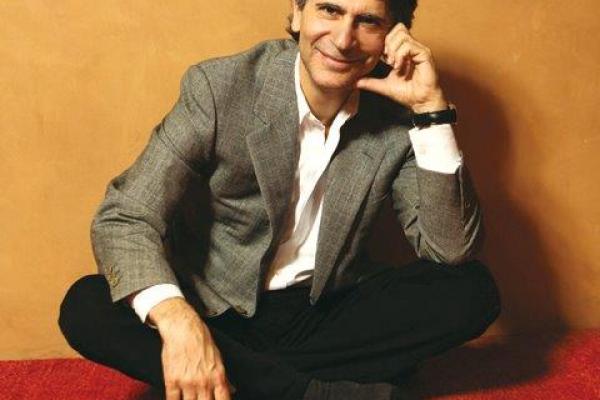

I spoke with James Tufenkian, founder of Tufenkian Foundation which serves to promote social, economic, cultural and environment justice in Armenia as it recovers from its genocide. I asked him about his connection with Sojourners, and how his work and faith intersect.

Ariana Denardo (AD): How did you get connected with Sojourners, and why did you decide to become a donor?

James Tufenkian (JT): My brother, a retired pastor, and I were having a series of conversations about the involvement of the church in social issues. He mentioned Sojourners, so I visited the website, read the magazine, and got interested. I found Sojourners to be the best, maybe the only organization I know of that works on social justice as Christians living out Christ’s example. It was natural for me to want to support that in different ways, one of them being as a donor.

Read the Full Article