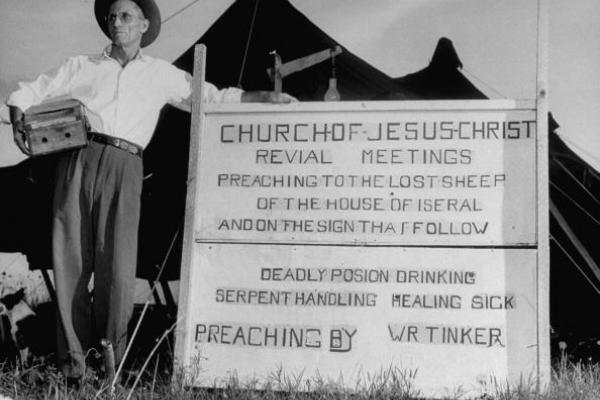

A recent piece on the Huffington Post's Religion page described the death of Pastor Mark Wolford, a Christian minister known for handling venomous snakes during his worship services to demonstrate the power of his faith. The stunt went south, however, after he was bitten on the thigh during worship and died at a hospital not long after.

The practice, though rare, is employed in a handful of Christian congregations in response to a literal interpretation of verses 17 and 18 in the 16th chapter of Mark:

And these signs will follow those who believe. In My name they will cast out demons; they will speak with new tongues; they will take up serpents; and if they drink anything deadly, it will by no means hurt them; they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.

There are several dangers this story raises, not the least of which, of course, is death by venomous snake bite. Such communities require public displays of faith that are meant to test the resolve of the faithful. And such practices are not restricted to backwoods protestant churches; some Catholics (and others) are enamored with the phenomenon on stigmata, where people exhibit physical signs of crucifixion, such as wounds on their hands or feet.

There’s the more obvious danger of putting someone in harm’s way by expecting them to perform a dangerous act to prove their faith. But there’s also the undercurrent of religious one-upsmanship, wherein folks are forever striving to be more daring, graphic or otherwise attention-grabbing. In addition to the potential physical danger, there’s the risk of pressing people to be deceptive in their faith practices, simply to enjoy the validation or admiration they seek, and which is held in such high esteem in these particular circles.

But beyond this, there’s the insidious danger of biblical literalism. First, there’s the social litmus test by which all in a literalist context are assessed. Put simply, if they believe every word of the Bible, as-is, they’re in. If not, well, best of luck to you. This kind of all-or-nothing approach naturally inheres a sort of group-think into a community, requiring everyone to toe a particular theological and social line “or else.”

It also places others easily in the position of judge and jury over another’s faith. After all, if you believe that God will protect His faithful from poisonous snakes, and then you die from a snakebite, what does that say about your faith? It must have been your fault.

This approach to faith ironically transgresses one of the cardinal Biblical rules about not testing God. Though I’m sure serpent handlers and the like would not see this as a test of God, the effective message is, “I’m going to do something unnecessarily, stupidly dangerous, simply to show that God will keep me safe.”

How is that not testing God?

The question that lingers is why we engage in such practices in the first place. It seems that it speaks both to our longing for affirmation and respect from our peers, as well as a longing to experience our faith in physical terms. We yearns to see God’s face, to touch physical evidence of the divine, to engage our human senses in the discovery of a perceptible dimension of the Holy.

But this, after all, is not what faith is about as I understand it. Faith is an orientation toward something rather than an arrival at it. Faith is a daily practice, not a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Yet we continue to try to define God, faith and the Bible on our own terms.

Yes, I’m as culpable as the next person; none of us can extract ourselves from the story. We are both witnesses to, and co-creators of, the ongoing story of Creator and creation.

Put more simply but less poetically, there’s no such thing as un-interpreted scripture. But when those interpretations put us and our faith practices on display, or when they put us or others at risk, we’ve crossed a line. While I believe there’s room in the Kingdom of God for a broad spectrum of understandings of God, there also are limits.

And when our faith places us either on a pedestal or teetering on the edge of an untimely death, we’ve surpassed that limit.

Christian Piatt is an author, editor, speaker, musician and spoken word artist. He co-founded Milagro Christian Church in Pueblo, Colorado with his wife, Rev. Amy Piatt, in 2004. Christian is the creator and editor of "Banned Questions About The Bible" and "Banned Questions About Jesus." His new memoir on faith, family and parenting is called "PREGMANCY: A Dad, a Little Dude and a Due Date." For more information about Christian, visitwww.christianpiatt.com, or find him on Twitter or Facebook.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!