Jul 18, 2013

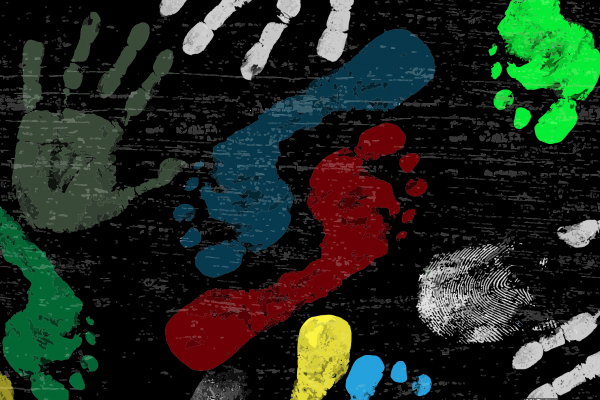

What better way to honor Nelson Mandela on his 95th birthday today than to reflect on his concept of Ubuntu? Ubuntu, a word from the Bantu languages of southern Africa — roughly translated “I am because we are” — sums up Mandela’s approach to leadership, incorporating a generous spirit and concern for the wellbeing of one’s community.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login